Paul Young is Digital Preservation Specialist/Researcher at The National Archives UK

The Challenge

The National Archives has recently been looking at the issue of transferring material from departments with Google Workspace Environments (previously GSuite). The rise in cloud document management has brought new challenges which require changes to existing processes and methods.

One of the biggest issues is dealing with the Google native cloud formats produced by the suite of collaborative Google tools, such as docs, slides and sheets. These require different methods of handling, as they exist as data that is rendered within the browser, rather than as distinct files. The original format cannot be exported and rendered as you would a Word Document or PDF file.

Recent TNA work

The National Archives has been looking at options for extracting metadata as well as exporting files (both native Google files and any other formats stored in Google Drive).

While the Google Drive browser UI gives you a fairly limited set of metadata, there is a wealth of other metadata which is accessible via the Google Drive API. Metadata fields which can be extracted via the API can be seen here. As part of a research project, we have been working on prototype scripts (which are available on GitHub) which could download this metadata using the Google Drive API and convert to The National Archives current metadata standards.

One of the key fields which can be extracted is an MD5 value, which allows us to follow traditional integrity checking processes to check the files have not changed during any export processes. However, native Google formats such as Google Docs do not have an MD5 value. This helps to highlight the difference between native Google formats and the more traditional formats which can be stored in Google Drive.

Google formats, why no checksum?

No checksum is held for Google Docs (Sheets, Slides or any other Google format) because they exist as data that is interpreted by Google and rendered within the browser, so they do not exist as a single definable format. Because they can only be opened inside Google's services, their original formats cannot be exported as you would a Word Document or a PDF file. If you have seen a .gdoc or .gsheet file these simply provide a link to open the file in your browser from within Google Drive, they do not contain any of the original data from the file.

Normal practice at The National Archives during transfer and ingest processes would be to prove integrity of the files via a checksum and preserve the file in its original format. With Google Docs this is not an option. This requires us to find another way of handling this material.

Exporting Google Docs

Jenny Mitcham (in the first of her series of blogs from 2017) explored the results of exporting a variety of Google Docs. Jenny carried out some tests on the various export formats to see how they compared. I conducted a similar test recently to see if any behaviour had changed. I used a small sample of files, comparing export outputs. This was done using files with similar characteristics to Jenny’s, but which also included ‘Suggestions’ which is comparable to track changes in Microsoft Word, full results can be seen here. Notes on some of the exports are included below.

|

Export format |

Comments |

|

Docx |

Similar to results from Jenny Mitcham. However, comments were no longer anonymised. Suggestion was retained. Page formatting often affects page numbers, Google Doc has more pages in its original format. |

|

ODT |

Similar results as Jenny Mitcham. Comments included. Kept suggestions. Page formatting often affects page numbers, Google Doc has more pages in its original format. |

|

|

Comments included at the end of the document but have lost usernames. Suggestions are not included in the export. |

|

HTML |

Comments added on at end, anonymised. Suggestions are not included in the export. |

This showed that while the results were similar, one change was that the Docx file comments were no longer anonymised. This demonstrates that Google Docs are always changing, and consistent behaviour cannot be guaranteed. For office style document and spreadsheets, the Microsoft or Open Office formats offer the most similar functionality. Another recent change has been the ability to upload docx and doc files and edit them within Google Docs itself. Google Drive does provide MD5 checksums for these files that can be validated on export. One aspect noted in Jenny Mitcham’s blog was that exports lose the metadata stored in Google Drive once exported (especially date metadata); although when combined with the information in a crawl of the API metadata, this can be negated.

Generally, the exports looked an adequate version of the original, Google is good at producing exports for standard office documents.

Exporting Google Sheets

With Google Sheets some of the issues which Jenny described in her test (see her blog) seem to have improved. For most of my examples, I received no error messages on opening the files. For simple spreadsheets, ODS and XSLX exports gave a good representation and preserved any comments. Though I did have one issue with a chart disappearing when exported to ODS. These export formats provide the closest functionality and accessibility to the original Google Sheet format. Where it gets interesting however is if the spreadsheet contains formulae which are specific to Google Sheets. There is a selection of formulae which exist only in Google Sheets, as an example there is a formula which you can use to run Google Translate over cell data. This website has a good list of these formulas.

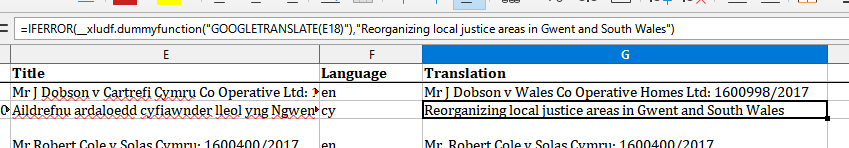

On export, these formulae cease to function, though often the data is exported. With the Google Translate example the formula is retained even though it is not functioning, however the data which the formula returns is displayed in the exported sheet. Below is an example from a Welsh translation.

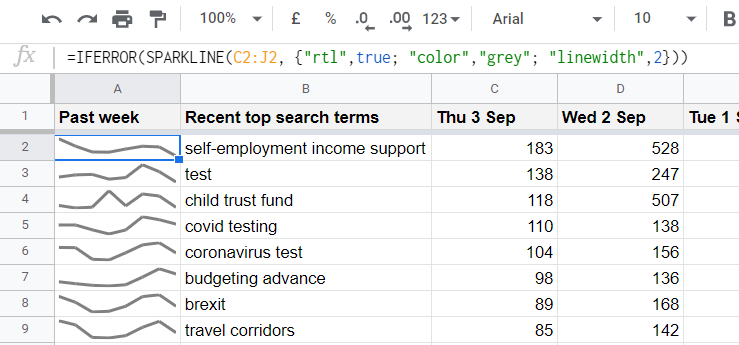

There are some scenarios however, where ODS and XLSX exports are not quite so complete. For example, Google Sheets and Excel both have Sparkline functions (where small line charts appear in cells), although they work in different ways. OpenOffice Calc does not have Sparkline functionality without an extension.

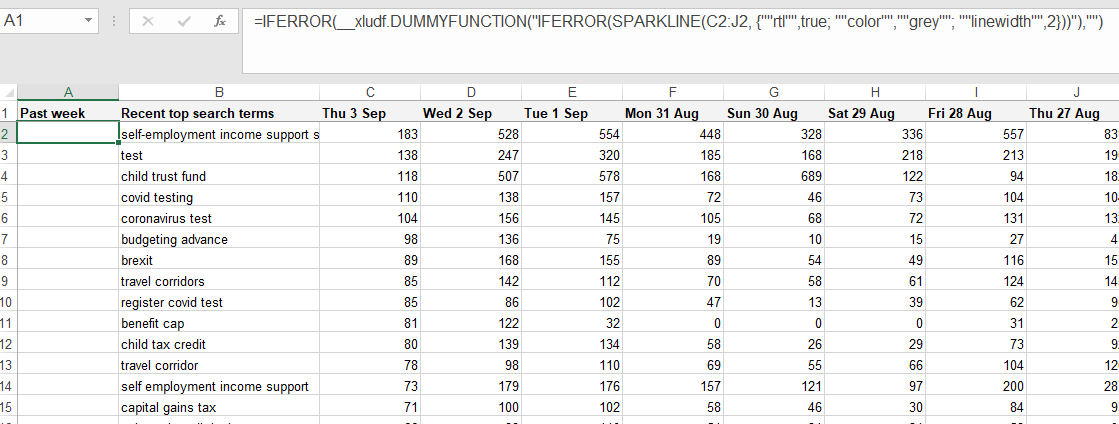

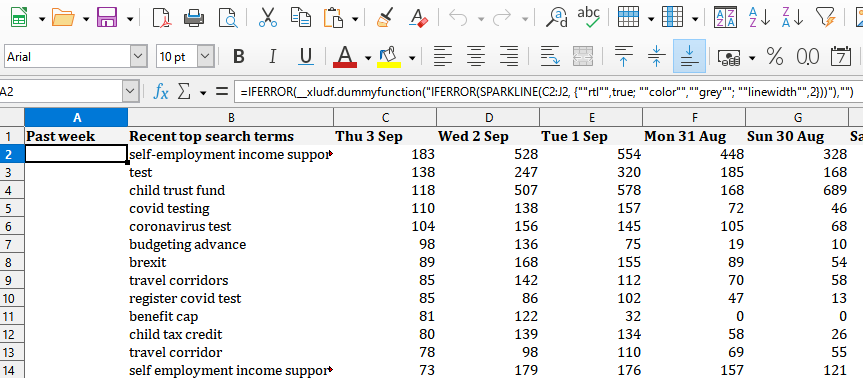

In the examples below we can see that both the ODS and XLSX exports do not show a complete representation of the original format.

Original Google Sheet

Original Google Sheet

Microsoft Excel (.xlsx) Open Document Format (.ODS)

Both formats show that while the original formulae are kept, they no longer function and the Sparkline visualisations completely disappear.

The examples below of the PDF and HTML exports show that these do a good job of keeping such visualisations. The downside is that a lot of the original functionality of working in tabular data, as well as the formulae used are lost. PDF exports also have a drawback in that hidden sheets do not seem to be included in any export.

HTML export from Google Sheets PDF export from Google Sheets

As with Google Docs, for standard documents an export of an ODS or a XLSX file will probably give a fairly accurate rendition of the original file. Problems occur with more complex files, especially ones using formulae specific to Google. Therefore, if preserving via export formats we plan to export in multiple formats. An export in an ODS format and an HTML format will reduce the risk of losing data during the export process.

Additional Google Formats (Slides, Draw)

There are a wide range of additional Google services which offer a variety of exports. The final two I want to briefly mention are Slides and Draw. Google Slides, like Google Docs and Sheets, supports export in similar office formats, ODS and PPTX. These offer a fairly good export compared to the original.

With Google Draw there is the option to export as PDF, JPEG or PNG file, which all offer a reasonable result. One thing to be aware of however, is that once exported any layered images will be flattened, which may cause issues depending on the image.

Web Archiving

Another option which could preserve their original functionality and feel is to capture these services through web archiving.

Conifer is being used at TNA to archive lots of complex things and could also be used to archive Google Docs. When used on some public Google Docs links capture was successful and it could be played back via a browser. However, this is not reliable at present and there are issues with scalability in using a browser-based tool like Conifer. There are also questions about how to capture documents from access-controlled environments, which presents further challenges to web archiving harvesting and replay technologies.

Why not leave them in Google?

If the files are changing on export why not leave them in Google Drive? Generally digital preservation practitioners think in the long term; they do not want to have files which are reliant on a single provider. While Google is unlikely to disappear in the short or even the long term, there is a reasonable chance that the different services or products they offer will change or disappear. Leaving native Google files in Google Drive could offer a short-term solution but as time passes there could be risks that changes to products could alter the way the documents are presented.

Continual change within these products may also affect whatever export processes an archive is carrying out, meaning that it is key for archives and the community to keep up to date with the latest developments in these services.

What does the digital preservation community require?

As described in this blog, there are multiple options when it comes to preserving documents created by the suite of Google tools. Most come with some caveats. The appropriate approach to take may vary from archive to archive depending on its collection criteria.

-

Scalable Web archiving approaches would offer a route to capturing and replaying Google Docs in their original form, especially for any public Google Docs links on websites.

-

Export formats can offer a way to preserve material without needing to be rendered inside Google systems, but how can we ensure the integrity of the capture?

Native Google formats also offer opportunities to preserve more information than previously possible with traditional formats like DOCX or ODS. The Draftback tool shows that Google Docs holds a complete history of the document, so technically you could preserve every keystroke. Preserving this level of detail may be desirable for some archives. Though this would create a large burden for archives having to review materials for sensitivities prior to making them available to the public.

There is also the question of what users or archives want? What will they need from Google formats in the future? Will they want to interact with documents in the same manner as in the original systems? Or are they more concerned about potential data loss via export formats? We should also be aware that similar concerns will arise in other services, Microsoft is planning ‘Fluid Office Documents’, which could have similar issues for preservation. Thinking about our requirements for Google formats now may lead to principles which could be replicated across multiple platforms in the future.

Google has shown a desire through conversations with The National Archives to work with the archiving community to look at preservation options. Given the number of directions which are available, a question I want to ask is what would the community consider vital characteristics to preserve within Google formats?

-

What features of a native Google format do you need to capture?

-

What features of a native Google format do you believe future users will need to access?

-

What metadata should be captured alongside the content?

-

What else could Google do to make it easier for you to preserve content created in Google Drive?

We have an opportunity to tell Google what we need from them in order to preserve the terabytes of digital information being stored and created in its formats. Please give us your thoughts so we can ensure that our digital heritage is preserved for future generations. It will also serve to make all our lives easier!

Get in touch with the DPC (jenny.mitcham@dpconline.org) with your thoughts/ideas/requirements or let us know if you would like to attend a focus group to discuss this issue with The National Archives and the wider digital preservation community.

Comments

Thanks Sarah, that's really cool!