Digital preservation requirements for procuring IT systems

This section of the Procurement Toolkit proposes the requirements that should be considered when procuring an IT system (for example, an EDRMS, DAMS or GIS), that may ultimately contain at least some records or digital content that need to be retained beyond the life of the system.

The aim of this work is to provide typical requirements relating to digital preservation that practitioners can contribute to procurement exercises for non-digital preservation systems at their organization. These requirements relate primarily to ensuring that digital content can be extracted from the IT system in question, along with necessary metadata, in a form that can be reused without dependence on that system. Justification is included to show why these requirements are important. Ultimately this work is about ensuring that IT systems purchased today have a digital content exit strategy and do not lock-in data when the system reaches end of life. Note that these requirements may need to be adapted to your local context.

-

Digital preservation requirements for procuring IT systems (download )

Business case hints and tips

![]() A summary of hints and tips on writing business cases and selling your proposal to your organization. Use this to ensure you create a positive and convincing business case.

A summary of hints and tips on writing business cases and selling your proposal to your organization. Use this to ensure you create a positive and convincing business case.

-

Prepare. Before you start your business case, make sure you know exactly what you are asking for, then do your groundwork to introduce the idea before making a formal proposal. This can involve activities like running workshops with a view to gaining staff agreement on areas such as scope, benefits and values. This will help you pitch your business case at the right level (budget, resource, language etc.) as well as gaining engagement and buy-in for the work with key stakeholders.

-

Know your audience. Understand the audience to whom you will be making your business case and tailor your language and messages to suit them personally, whilst also appealing to organizational drivers! Also consider institutional sensitivities (e.g. other organizations they compare themselves with) which could act as a motivator or a deterrent, as well as any external contexts (e.g. the 'digital shift' post covid) which might influence decision making.

-

Use the right language. Talking or writing about digital preservation can involve the use of some technical terms. Try to talk about digital preservation in ways that your target audience can relate to. (e.g. Digital preservation is 'gold standard' information management) and avoid scaring people off with jargon. Consider whether you should even use the term "digital preservation" at all. Discover how your audience describes it and mirror their terminology.

-

Keep it focused and relevant. For those unfamiliar with digital preservation, it may seem intangible, long term and even a bit boring(!) when, in fact, digital preservation can support all parts of a business process. Therefore, use careful definitions which are relevant to your audience. It can be helpful to make use of diagrams or visualizations for expressing complex information and you should aim to describe issues in a way that will have the broadest appeal. If you discover that a single large business case is not within scope, consider breaking your business case into multiple projects which may have a better chance of being accepted.

-

Network. Once you know your audience, take every opportunity before, during and on completion of the business case to make your case personally to key people. Your aim is to win over key decision makers before your business case is even formally assessed. If you are not able to communicate with the decision makers directly, it can help to get other members of senior management on board to convey the message for you. And, make sure anyone mentioned in the business case knows about it in advance of reading it!

-

Stay positive. Take care to focus on what will change or be better as a result of the investment you are asking for; rather than trying to sell "digital preservation" itself. Equally, try and gain a balance between the benefits and the risks, don't be too alarmist or focus too much on a negative vision e.g. 'digital black hole'. And carefully explain context to avoid the accusation that you are creating a problem to solve.

-

Make your costing realistic. Despite all of your best efforts to point out the benefits of your digital preservation activity, for many organizations the most critical factor is the COST. This needs to be acceptable to the organization. Do your preparation to make sure you are making realistic demands.

-

Use evidence. Make sure you can back up any claims that you make using examples from within your organization, case studies from other organizations, authoritative sources and hard data.

-

Learn from others. Work with (or at least consult with) someone who has worked on other successful business cases at your institution. Once you have drafted your business case, test it on them before you submit it, and be open to suggestions and feedback.

-

Practice. Part of the business case submission process is likely to include a presentation. Use clear concise slides and practice your pitch on your experienced business case colleague (see tip above) to make sure your messages are clear and understandable.

-

Play the long game. Be prepared to re-submit (or for it to take a long time before you gain approval). Your business case might be perfectly good, but there may be other competing priorities at the time you submit. In many cases you will be able to resubmit your business case again, and you can use the additional time to do further research and refinements, but be aware that some organizations limit the number of submissions. Do your homework to find this out.

Further resources on business cases

A list of additional guidance materials relating to business cases. Use this as a reference point for further reading on the subject.

-

What has been found to be the most effective alternate term for “digital preservation” when communicating beyond the library and archives community? (Stack Exchange). A discussion on what alternative terms to “digital preservation” have been most effective.

-

Writing a Good Business Case (The Royal College of Radiologists). Guidance on business case writing from outside of the digital preservation field.

-

Digital Preservation Series. Part 1: Making the Case (APAC). Section 7 outlines key steps for writing a business case including suggested document headings.

-

A Guide to Making the Business Case for Digital Preservation (Preservica). All round guidance on making the case for digital preservation.

-

Producing a business case for digital preservation and long-term access. A how-to-guide for heritage and higher education (Arkivum). Guidance on making the case, with suggested benefits.

Template for building a business case

This section provides guidance on the content that will be useful to include in your business case, but it will likely need to be adapted to the structure used in your organization’s template.

This section provides guidance on the content that will be useful to include in your business case, but it will likely need to be adapted to the structure used in your organization’s template.

Executive Summary

A concise and persuasive summary of the rationale for undertaking the proposed digital preservation work.

The Executive Summary highlights key elements of the longer business case, ensuring that the reader is made aware of the high-level aims and benefits of the work as well as outlining who is requesting the work. An effective Executive Summary should present this information in a clear and concise manner.

The Executive Summary is often called the most important part of a business case, so time invested in crafting and reviewing this section will be well spent. The Executive Summary sets the tone and should entice the reader to actively engage with the rest of the business case. When writing an Executive Summary, keep the intended audience in mind at all times. Consider what background knowledge the reader already has and what you will need to explain to get your message across.

Further considerations:

-

Before submitting, do a final check to ensure that your Executive Summary accurately reflects the full business case. There should be no surprises for readers when they scrutinize the rest of the proposal. It may be easier to write the Executive Summary after writing the other sections of the business case.

-

Developing an elevator pitch can help you to identify the main messages which you want to convey in the Executive Summary. See these example pitches from digital preservation practitioners at the SPRUCE mashup events.

-

You may also want to create a separate slide deck of the Executive Summary section that can be used when presenting to stakeholders.

Problem Statement

A description of the issue, challenge or situation that the business case seeks to address.

The problem statement should outline the challenging aspects of the current situation and address why it is important that change is enacted (this will also feature in the section on risks). It should be written with the perspectives and concerns of those key stakeholders, and/or from the point of view of the beneficiaries of whatever investment is being proposed. To generate ideas for this section, it may be beneficial to brainstorm with a small group of engaged colleagues or stakeholders (4-6 people) with each person writing down what they perceive to be the problems that need addressing. This can then be used to identify common themes or forms of wording.

The focus should be on existing and demonstrable problems. Ideally the problems should be quantifiable and it should be possible to describe a timeframe over which they have been occurring. It should be possible to identify:

-

Who is experiencing the problem?

-

What is the nature of the problem?

-

Where is the problem occurring?

-

When (for how long) has it been problematic?

-

Why is it a problem (what impact is it having)?

At this point, it is not necessary to recommend a solution. This will be introduced and considered in the options section below.

Background and Context

The organizational context that provides a relevant background and supporting evidence to your business case.

The readers of your business case may have a partial, out of date, or incorrect understanding of the relevant context and background to the business case – it may be useful to include this information to ensure everyone is working from the same page. This is also an opportunity to demonstrate that you have properly researched and understood your organizational setting before asking for investment and change. The Understand your digital preservation readiness and early stages described in the Step-by-step guide to building a business case provide thoughts on how to research and capture useful contextual information.

A background and context section may include:

-

A description of current digital preservation capabilities. This may be qualitative or quantitative, or both. It could include details around staffing, systems, training, membership of professional organizations, accreditation and certification.

-

Work to date. This may include a description of previous relevant business cases, projects, policies, strategies, delivery of training and guidance, implementation of systems and workflows. Acknowledge what has worked well, what has not, and lessons learned. Highlight where investments in this area have seen good returns.

-

Scope of digital content. Explain at a high level what digital content is in scope and a summary of key characteristics. It may also be useful to explain what is not in scope, and why. This section could take the form of an appended table or diagram. Consider including:

-

what digital content is in scope for discussion

-

how it has changed and is projected to change over time (e.g. in format, scale, complexity)

-

what systems are used to create, manage and store the content

-

who creates it

-

who owns it - the "custodian"

-

how long it must be kept for

-

any relevant governance in place

-

-

Summary of a maturity modeling exercise. Identify your organization’s digital preservation maturity using the DPC Rapid Assessment Model. This data can also be used as a baseline for establishing or measuring changes in capacity or maturity post implementation of the business case.

-

Explain how digital preservation relates to your existing mission, strategy, and policy documents. This will help to demonstrate that you understand your organization’s responsibilities, requirements and drivers. Establishing that these implicitly or explicitly require an improvement in digital preservation capacity/maturity will be useful in making your case.

-

Identification of key stakeholders. Describe the key staff, committees/groups, users/customers, and other stakeholders who will be affected by your business case. This could include digital preservation specialists, IT staff, project management staff, procurement staff, steering groups, creators and users of digital content, and partner institutions. This could take the form of a diagram or table.

-

Describe headline disasters, risks, and missed opportunities relating to digital content at your organization. The risks and missed opportunities may have already been identified by colleagues, external audits, customers/users, and other stakeholders. These could include previous data loss, reputational damage or legal damage due to poor digital preservation practice at your institution. There may also be examples where good digital preservation practice has previously “saved the day”, minimized the impact of a risk or issue, or protected your organization’s reputation. Note any changes in the external context of your digital preservation work, such as changing stakeholder expectations, societal shifts, or national and international developments.

Options

A careful assessment of the potential approaches for addressing the problem statement, with a recommendation for the best option.

The amount of detail to include will depend on the size of the proposed project and the level of information typically expected within a business case at your organization. Some organizations use an explicit methodology for options appraisal, which may for example involve assessing implementation costs, ongoing costs and savings resulting from the investment. Some costs and benefits might be easier to identify than others (e.g. financial savings vs. a cultural change within the organization) but it is helpful to describe how any costs and benefits will be measured and assessed. As a minimum it will be useful to outline different costed options and provide evidence as to why one of the options has been selected as the best way forward. Costs will be addressed in more detail in subsequent sections, but it might be useful to provide broad cost categories of low, medium or high investment for each option. If appropriate, more detail could be provided as outlined below:

-

A high level description of requirements for the work that the business case seeks to address. These requirements will act as the criteria upon which the different options can be evaluated.

-

A description of the different options that are to be considered for solving the problem statement. This should include a "Do nothing" option that can be compared with the proposed solution upon which your business case is focused.

-

An assessment of the different options against the requirements. Costs, risks and benefits of your preferred option will be described in more detail below, but this is a useful opportunity to show what benefits your preferred option offers compared to inaction and/or any other alternative options.

-

A recommendation for which option is to be pursued. An honest and fair evaluation of the options, based upon clear evidence, will increase the chances of your business case being accepted. This analysis might be covered in a dedicated section. See Cost/benefit analysis, below.

Implementation Plan

A description of the activities that will be undertaken if your business case is successful.

The necessity for an implementation plan will greatly depend on the format of your business case and the level of detail required by stakeholders. A plan can simply be an outline of the activities (which will ensure your proposal is implemented successfully) through to an in depth description of execution such as specific milestones, deadlines and targets. Your background research should reveal what level of detail is expected for a business case of the scope you are considering at your organization. You may find that other aspects of your business case (such as the resourcing/ financial analysis) will be important in supporting your business case plan. Note that if your organization uses a particular project planning process or standard, it may be important to align your implementation plan with it.

Your implementation plan may include:

-

Outline of Scope. Providing initial detail of the scope which is encompassed by your business case plan will help you with the entire planning process. Providing this information will also make it easier for stakeholders to understand what your business case will and will not achieve and how it will link with your aims and objectives. Larger projects will potentially change as they progress from start to finish. This could be the result of a change in circumstances, budget, availability of resources etc. Ensuring that the scope of your implementation plan has been outlined in the first instance will help to avoid scope creep (where one or more aspects of a project require additional time, resource or budget due to poor planning). However, it can also make it easier to ensure that informed and necessary changes can be approved by the relevant stakeholders if needed. Outlining the scope of your business case does not need to be daunting, you simply need to set out the boundaries.

-

Objectives. It is important to clearly outline what your business case will achieve. Including a brief set of objectives can make it clear to stakeholders what will be accomplished. These objectives should be measurable. Below are a few ways in which your objectives could be presented:

-

SMART Objectives. ‘SMART’ stands for Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-bound. These prompts can help you to develop attainable goals and objectives for your business case plan.

-

Targets. Details of the business case targets would include a set of fixed goals which would be reached during the course of implementing your business case.

-

Milestones. Objectives can be broken down into a number of milestones, which are a specific point in time that is used to measure the progress of your implementation.

-

Timeline. Presenting the main objectives of your plan on a timeline will allow you to show key dates alongside the relevant target. A timeline can be more easy to digest, as long as you do not have a particularly complex plan (in which case something like a Gantt chart would be more beneficial in helping you to lay out each aspect individually).

-

-

Dependencies and Assumptions. Dependencies relate to other organizational activities, elements of infrastructure, or other factors external to the activities described in the business case but on which success of the plan is dependent. Assumptions refer to elements of the plan where there are expectations about issues such as decisions that will be made, elements of work that will be carried out, or resources that will be made available. The dependencies and assumptions made during the planning stages can be closely linked to the risks of a business case. If there are heavy assumptions made in the early stages of a plan, this can lead to issues during execution. For this reason, it is important to consider how these decisions made can affect the viability of the business case as a whole.

-

Roles and Responsibilities. Providing a list of roles and responsibilities will help you to identify the resourcing levels needed in order for your business case to be implemented successfully. These will depend on the number of people who are involved with executing your plan and what is expected of each person. A list of roles accompanied by bullet points describing the activities each role is responsible for can be an easy way to show this information. Defining roles and responsibilities at an early stage can help to avoid confusion when executing the plan. You may find that roles and responsibilities may develop and change multiple times during the planning stages, however, you should be able to avoid adding to or changing them during the execution of your plan.

-

Project Governance. Consideration of project governance should accompany planning of your roles and responsibilities. The two aspects are closely linked and it is important to think about how each of the roles should feed into the other and whether there is a need for a decision making hierarchy, escalation routes, a steering group, or similar.

-

Fix Forward Planning. Thinking about a "fix forward" for your business case is crucial in ensuring that whatever you implement can be updated, utilized and maintained following the initial launch or implementation. Whatever you plan to do, this may cause changes in basal costs for your organization. Any changes to this need to be discussed in your risks or benefits. You should aim to avoid a situation where time and resources are spent implementing a new system or process only for it to fall into disuse. For example, if a business case seeks to establish a new digital preservation system, then considerations should be made for:

-

Use. Who will use the new system? Have they been trained to a competent level such that the system will be used and updated? If this has not been considered, it would be beneficial to check this before submitting the plan or budget estimate.

-

Resourcing. Who will keep it updated? Does this require the creation of a new permanent position within the organisation?

-

Maintenance. Will there be any ongoing or regular costs associated with maintaining the system that you have implemented? If so, this would need to be factored into the basic running costs of the organisation.

-

Licencing/leasing. This is detailed further in the Resourcing/Financial Analysis section and could be related to licensing of software or leasing of specific equipment etc.

-

Exit strategy. Planning for the end of life for a new system will prevent costly digital preservation issues. See the DPC Digital Preservation Procurement Toolkit.

-

Benefits

The benefits that will be delivered by the work outlined in your Implementation Plan.

The benefits section of your business case should identify and describe the financial and non-financial benefits of your digital preservation proposal that will justify the investment. A benefit is a measurable outcome of an action or decision that contributes towards reaching one or more of your organization’s objectives. Benefits can be described or categorized by the timescale with which they will be realized.

By researching and understanding your organization’s Strategic Plan, you can make sure the benefits you include align with the organization’s objectives and selling points or with issues that will strike a chord with the reviewers of your case. They could include:

-

Accountability and transparency

-

Authenticity of records and holdings

-

Business continuity/management of operational risk

-

Compliance with legal regulations, best practice guidelines and specifications

-

Cost efficiencies and/or avoidance of penalties

-

Enabling research

-

Information security

-

Integrity and operation of systems and/or technology

-

Managing and maintaining a good reputation

-

Increased revenue

-

Safeguarding the corporate or cultural memory

-

Service improvements

-

Reduced carbon footprint

-

Meeting funder requirements

-

Protection of past investments

The next section of this toolkit, Example benefits and risks for typical digital preservation business cases, provides benefit and risk statements for the following scenarios:

-

Developing a digital preservation strategy/roadmap

-

Increasing staffing complement

-

Repository migration to cloud

-

Procuring a new digital preservation system

For further examples of selling points to include in your business case benefits, see:

-

The Executive Guide on Digital Preservation with benefit statements which relate to different organization types.

-

The Keeping Research Data Safe project, Benefits Framework and Benefits Analysis Toolkit.

-

Preservica’s A Guide to Making the Business Case for Digital Preservation.

-

Arkivum’s Producing a business case for digital preservation and long-term access.

If you have used a maturity modeling tool like the DPC Rapid Assessment Model (RAM) earlier in your Business Case to demonstrate the need for investment, you can use the stages or steps within this to develop a Benefits Realization Plan which identifies how and when the benefits will begin to be realized.

Risks

The risks associated with the execution of the implementation plan if the case is funded and the risks faced by the organization if the case is not funded.

Identifying and understanding risks should be an important part of any organizational activity. Mitigating the risks identified through proactive management reduces the likelihood of them occurring and/or reduces their impact when issues do occur. As it is a process that is commonly used across many types of activities, it is a useful tool for sharing information in a format familiar to people working across different disciplines or areas of an organization. An assessment of the risks faced is, therefore, an essential part of any business case as it helps those evaluating the business case to understand the potential impact of the work even if they are unfamiliar with the details of digital preservation.

There are two groups of risk that you may wish to discuss within your business case:

-

Risks associated with the execution of the Implementation plan, should the business case be funded.

-

Risks faced by the organization if the business case is not funded.

A description of the risks that would be faced during the execution of the options set out in the business case will allow those assessing the business case to compare the potential negative impacts of the work with the benefits that will be accrued. The risks included here should align with the implementation plan as described in a previous section. The risks covered might include problems occurring that would cause delays, how staffing changes might affect progress, or technological risks faced.

Setting out the risks faced by an organization if the business case is not funded can be a particularly persuasive part of making your case if the risks faced are significant (e.g. they affect revenue streams or may result in the failure to meet legal obligations) or your organization is particularly risk averse (e.g. the risk of data loss might result in harm to a organization’s reputation which could in turn affect funding). If you plan to include such risks, it is important to ensure the risks described are realistic and relevant and to avoid an approach that might be described as “scare-mongering”. Note that it may be more suitable to include these kinds of risks as “dis-benefits” in the benefits section of your business case.

Depending on the organization or project in question the business case may only need high-level risks to be identified, whereas others may require a full, detailed risk assessment to be carried out. A more in depth risk assessment exercise might identify the likelihood and impact of each identified risk. Scoring and multiplying together the likelihood and impact will give a raw risk score. Risk mitigation activities may then reduce these scores, providing an indication of most significant risks for further consideration.

Resourcing/Financial Analysis

A budget for implementing the activity outlined in the Implementation Plan.

Completing a project within the proposed budget is often regarded as one of the key success factors. So it is important to ensure that any financial information included in your business case is as accurate as possible, and that any proposed costs can be explained and justified.

Before you begin, make sure you know who is financially sponsoring your proposal and who will control any financial decisions about the project. Setting a clear budget will also help manage stakeholder expectations, and identify when key expenditure is likely to take place (this is especially important in organizations where resources are shared between several activities that are taking place simultaneously).

Developing the budget for your business plan is likely to be an iterative process, and you should be prepared to seek out advice from colleagues if possible. You should also be aware of any organizational policies or constraints on how proposals should be costed, when and by whom financial figures need to be approved and what are acceptable levels of contingencies.

Your budget should be comprehensive and realistic. The activity described in your Implementation Plan may depend upon resources from elsewhere in your organization. This should be identified and costed, even if direct funding is not being sought as part of your proposal. This will reduce the possibility of these resources being over-allocated and impacting on the success of your project.

Typical costs to include are:

-

Staff. Include costs for each person/role (make sure you follow your organization’s guidelines on costing salaries, for example, how any salary increments during the lifetime of the project will be reflected). Find out if new roles, consultancy services, or contractors need to be costed for, according to particular metrics. For fixed-term contracts you may need to factor-in the cost of redundancy payments.

-

Equipment. If your proposal will require the purchase of new equipment, seek advice on any organizational guidelines around procurement. Find out how you should identify capital expenditure, maintenance costs, depreciation etc.

-

Materials/consumables. Include the costs of anything which will be consumed by the work of your project.

-

Licences and fees. The costs of acquiring software and any support/maintenance fees throughout the lifetime of the project. If these costs will continue beyond the timeframe of your proposal this should be made clear.

-

Training. Include the cost of any additional training that staff might need to undertake the work outlined in your proposal. You may also want to include provision for any training that your project will need to deliver/offer to others to ensure that the outputs of the work can be successfully adopted.

-

Travel. Include estimates for the full travel and subsistence costs that might be incurred by staff during the lifetime of the project. Organizational guidelines and constraints may apply to levels of funding that are permitted for certain activities.

-

Overheads. Find out if your organization will expect to see a contribution towards any overhead costs (e.g. administration costs, IT, facilities) and how these should be shown in your budget. Some organizations apply a predetermined percentage amount for overheads.

-

Contingency. Most organizations will have clear guidelines on acceptable levels of contingency funding (e.g. to take into account any unidentified work or currency fluctuations). If you need to diverge from these guidelines, perhaps because you have identified particular risk factors, this should be clearly justified.

Bear in mind that the list above is not exhaustive. Looking at previous (successful!) business cases and consulting with colleagues within your organization can be extremely helpful in making sure that you have covered all the right costs in a way that is likely to be acceptable to the decision-makers within your organization.

Typical reasons for budgets being judged inadequate, or for shortfalls occurring during the lifetime of your project include:

-

Poor estimates of the resources required for the work, or lack of justification for the costs that have been included.

-

Missing costs. Again, consulting with colleagues and learning from previous proposals and projects is the best way to ensure that you do not overlook any costs which might impact the work or overall success of your proposal.

-

Failing to take into account resources that are shared, or dependencies on other parts of the organization.

Consideration should also be made regarding any ongoing costs which would result from implementing your business case. As already mentioned, there may be ongoing licencing or lease costs which extend past the deadline of your execution plan. These costs would most likely arise from implementing new software or equipment which is acquired on a lease basis. Other costs which may carry over include additional staffing required to update or maintain a new system or the need for additional support from existing IT teams for example. If this is the case, then it should be outlined in the business case so that stakeholders and decision makers can be made aware.

The authors of some business cases choose to include a short statement of the “costs of inaction”, reflecting the impact on the organization if the work outlined in the proposal is not undertaken. This can be a persuasive strategy, but risks the accusation that any costs outlined in this way are merely hypothetical – so if you decide to include a section along these lines make sure that as far as possible you can justify any claims that you make (e.g. by pointing to evidence of previous costs incurred as a result of inaction).

Cost/Benefit Analysis

An analysis of the benefits of each option minus the costs, indicating the best option to implement.

The purpose of including a cost/benefits analysis section is to demonstrate that sufficient consideration has been given either to alternative ways forward, or to taking no action at all. In previous sections, the costs and resourcing for the proposal have been set out, and the likely benefits have been itemized. From an organizational point of view, what this does not make clear are the opportunity costs. In other words, what alternative benefits might be realized, and what opportunities could be exploited, if the same level of focus and investment that the business case proposes is deployed elsewhere.

It is unlikely in a digital preservation business case that a simple calculation is possible whereby the costs of action can be set against a quantifiable financial figure for the benefits that may be realized. Calculating the cost of a digital preservation system implementation project should be possible, but understanding all of the ongoing recurring costs is very challenging. Meaningfully comparing those costs with other organizations is extremely difficult. Quantifying tangible benefits is hard, but applying metrics to intangible benefits is impossible.

A balanced narrative is required that acknowledges some of the complexities of coming to a decision. There may well be more indirect costs involved for the organization that are not listed in the section above, such as the effort required across the organization to engage with digital preservation, or the overhead required for successful collaboration. This can be offset with the tangible and intangible benefits, but also some further elaboration of how the proposal positions and enables the organization to succeed.

A cost/benefit analysis should consider how strategically or tactically important it is for the organization to take the steps proposed. It is a chance to reflect, reiterate and summarize the overall short, medium and long-term value of the proposed activity.

Example benefits and risks for typical digital preservation business cases

![]() This section provides example benefit and risk statements for four typical digital preservation scenarios. Use this to build a convincing and realistic proposal.

This section provides example benefit and risk statements for four typical digital preservation scenarios. Use this to build a convincing and realistic proposal.

The four scenarios are:

-

Developing a digital preservation strategy/roadmap

-

Increasing staffing complement

-

Repository migration

-

Procuring a new digital preservation system

The statements provide suggestions that can be developed into fuller descriptions that take in your particular organizational context. Note that these examples are not considered to be comprehensive and should not be included in a business case without careful consideration. Many of the risks may need careful consideration that results in changes or mitigations in your Implementation Plan rather than explicit articulation as a significant risk to the project.

Developing a digital preservation strategy/roadmap

Potential benefits and risks associated with developing a new strategy or roadmap for digital preservation within a particular organization.

Benefits |

Risks |

|

|

Increasing Staffing Complement

Potential benefits and risks associated with increasing the digital preservation staffing levels with new roles.

Benefits |

Risks |

|

|

Repository migration to cloud

Potential benefits and risks associated with migrating from a home grown and on-premise digital preservation system to a cloud hosted system.

Benefits |

Risks |

|

|

Procuring a Digital Preservation System: Benefits and Risks

Potential benefits and risks associated with procuring and establishing a new digital preservation system.

Benefits |

Risks |

|

|

Step-by-step-guide to building a business case

![]() An outline of the the main steps to follow in constructing your business case including research, drafting, validation and delivery. Use this to plan out how you will develop your proposal.

An outline of the the main steps to follow in constructing your business case including research, drafting, validation and delivery. Use this to plan out how you will develop your proposal.

1) Establish a foundation for your business case

Having the right foundation in place from which to launch a business case can be critical, especially if your organization is relatively new to digital preservation. The first section of this toolkit, Understand your digital preservation readiness, provides a detailed discussion of actions that may be useful to undertake before developing a business case, including:

-

Modeling your digital preservation maturity levels

-

Gaining an awareness of useful context and previous digital preservation track record

-

Understanding your staffing and skill levels

-

Developing a digital preservation policy

-

Establishing a digital preservation steering group

2) Perform pre-business case research and planning

In order for your business case to be successful, it is important to gather some key information about your organization and its stakeholders before you start writing. Initially you could establish expectations for the business case itself by:

-

Finding someone who has submitted successful business cases at your organization and learning from their experience

-

Understanding how much research/preparation is appropriate for this business case

-

Understanding the organization’s expectations for a business case

-

Establishing whether the organization expects you to use a specific template for your business case?

-

Understanding the format (text, diagrams, tables, presentations) and extent (one-pager, 30 pager, elevator pitch, 10 minute presentations etc.) for different audiences.

-

Identifying organizational allies who can support the research and development of your business case. For example see “Digital Preservation and Enterprise Architecture Collaboration at the University of Melbourne” page 155.

3) Understand your organizational context

Understanding the context within which your business case will function is an essential part of preparing to develop the case itself. It is important to factor in the many different aspects of your organization that your business case will depend on. A PESTLE (Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental, and Legal) analysis is one way to structure and guide an assessment of these contextual issues but some critical elements to consider are discussed in more detail below.

4) Align with your organization’s mission and strategy

Any business case should further the broader aims of the organization, which makes it essential that you align your proposal with current strategic objectives. Typically these will be described in an organizational strategy or policy, but also perhaps in lower level departmental or sectoral strategic plans. There may also be a wider organizational mission that should be considered. Your business plan stands a much better chance of success if you can clearly demonstrate how it will advance these organizational objectives either directly, or by providing enabling actions that will provide the foundation for objectives to be achieved. So ensure you understand your organization’s objectives and ideally gain a feel for the decision makers opinion on current priorities.

Some organizations will have established policy frameworks which can define constraints within which operations are conducted. Alignment with a digital preservation policy may prove beneficial (see Understand your digital preservation readiness).

Growing concerns about the impact of our actions on the environment and the climate make it especially important to consider how the activities outlined within a business case might have an ecological impact. Most organizations will have an environmental policy which should be considered carefully in relation to your business case.

5) Identify your audience

Before you start writing your business case, you need to determine your audience(s) so that you can adopt the right tone and language, as well as being prepared with the right background knowledge. This will ensure that your document is impactful. Consider the following: which organizations, departments or individuals will assess your business case? Which parts of the organization (like teams or committees) will be affected by it, and to what extent? By identifying the people to whom you are presenting your business case, you will gain a better understanding of your audience and their priorities. Think about who will be evaluating your business case or making the decision to implement your proposal, even if they are not a part of your organization. These external stakeholders might have different needs and expectations. Other practical tips include:

-

Network and find a champion for your business case amongst the decision-makers

-

Be mindful of staff turnover - make the most of time spent courting champions, and don’t rely too much on one person

-

Be aware of your organization’s appetite for risk, and don’t over-promise.

-

Identify “hooks” that may play well to key stakeholders, e.g. avoiding reputational risks or facilitating a favored project. And at the same time avoid topics or arguments that may not play well with key stakeholders.

6) Choose the right moment to develop and submit your business case

Choosing the right time to develop and submit a Business Case can be crucial in achieving success, aligning with organizational processes, avoiding distractions and maximizing the potential support for building your case.

The business case should not come as a surprise to anyone and stakeholders should ideally have been brought on-board with key elements of the proposal as much as possible before they see the detail.

There may be constraints on when you can submit a business case within your organization’s planning and funding cycles. If there is insufficient funding left in this cycle, then it may, for example, be more realistic to delay a business case until the next funding year. Some organizations have specific cycles and deadlines for submitting business cases on a quarterly or annual basis.

There may be optimum times for building a Business Case, such as when there is better availability of your business analyst support staff and other stakeholders who can make a useful contribution.

Avoiding periods of busy, or peak activity within your organization could be important. There may be periods of organizational downtime, for example outside term times at an academic institution. Staff turnover might leave critical posts empty or lead to the loss of critical champions for your business case.

7) Develop a realistic budget

Decision-makers will want to know how much money you will need to realize your plans. It is crucial you provide them with a clear overview of all costs involved, including staffing, training, procurement, maintenance, and development. Make sure you have an idea of available budgets before you start with your business case, for example by looking at previous examples for similar activities or projects within your organization. Consider the following questions:

-

Does funding work on a project basis or can a new and permanent funding stream be established?

-

Which components of the project will your organization provide funding for?

-

If your organization has any guidelines or constraints on levels of contingency etc., it is vital that you keep to these.

-

Consider breaking your proposal into separate phases, each with clearly defined objectives and success criteria if you think that will be more acceptable to your organization than making a significant one-off commitment to fund a single large proposal.

8) Draft your business case

The roles and responsibilities for writing the business case should be clear to everyone across the organization. This may be straightforward for a small organization, but may involve more people as the size and scale of the proposal increases. Prior to embarking on the full business case, options should be explored to establish whether there is scope for a pre-business case to be presented without detailed costings and other time-consuming content being included. This ‘concept document’ can be used to test the organization’s appetite for a proposal (focusing on a SWOT analysis, strategic fit, need and viability) to make sure the time invested in developing a business case is not wasted.

When it has been established that the full business case is required, the sponsor of the proposal (ideally someone as senior as possible in the organization) should authorize commencement. Work should then begin to populate the most appropriate template with well-written, clear and focused content.

By the time writing starts, the key facts, evidence, costs, benefits, value, impact and other detailed areas of the proposal should all have been established. But it may be appropriate for the designated lead author to ask for specialist input from other key people (e.g. IT, finance, HR, third-party providers, technical writers) to ensure that the content and language is accurate and effective. See the section “Template for building a business case” for more help with the detailed content of your business case.

The document will almost certainly benefit from being checked by at least one person who can objectively assess the proposal without confirmation bias, especially if they have prior experience of assessing other business cases. Authors should approach the creation of the proposal with a flexible mindset and be open to ideas and changes to content and structure as the proposal comes together. Independent advice and feedback on your business case might be especially valuable. If possible seek guidance from the Digital Preservation Coalition and/or your peers at other organizations.

In many instances, organizations may prefer to initially respond to a summary pitch (often a slide deck) that represents the fuller proposal. The quality, clarity and persuasiveness of this summary is a critical component in establishing the value of the idea. If the purpose of the pitch is to provide a decision-making group with a foundation for discussion on the merits of the idea, it is vital that they start that discussion with positive feelings about the effort that has gone into drafting the proposal.

Understand your digital preservation readiness

This section considers what context and preparations are needed before producing a business case. Use this to establish the best foundation for your business case.

Establish your level of digital preservation maturity

Your organization’s digital preservation maturity can be quickly identified using the DPC Rapid Assessment Model (DPC RAM) which provides a set of organizational and service level capabilities that are rated on a simple and consistent set of maturity levels. The model enables organizations to monitor their progress as they develop and improve their preservation capability and infrastructure and to set future maturity goals. Understanding your maturity level helps in identifying gaps in current capability and areas to be developed in the future.

Understand the history and track record of digital preservation at your organization

Researching the history of digital preservation work at your organization can provide context for your business case, avoid previously encountered pitfalls and ensure learning from previous work. In particular, you should seek to understand and acknowledge investment (e.g. in systems, staffing, training, professional organizational membership) successes, failures, and missed opportunities:

-

Have there been digital preservation business cases at your institution before? If they were successful, can you show that the money was well spent? If they were unsuccessful, can you address or at least acknowledge what went wrong in any new business case?

-

How has your organization’s digital preservation capacity changed over time? You may be able to establish this with DPC RAM scores (see above).

-

Make sure to acknowledge any existing investment in basic digital preservation services like digital storage, systems, staff, and training.

-

Check whether those responsible for IT provision are aligned with the need for a digital preservation solution and understand what value it brings in addition to storage and fixity.

Assess organizational policies that might impact significantly on future digital preservation activity, including the need for a dedicated Digital Preservation Policy:

-

Do you have existing policies that establish a requirement to preserve digital content e.g. collection policies, records management policy, open access policy.

-

Consider whether any other policies will be relevant e.g. closure periods or embargos, IPR, data protection, environmental or potential liability issues.

-

Do you have a Digital Preservation Policy? Establishing a policy can provide a helpful foundation from which to build further infrastructure and activity, as well as acting as a useful advocacy tool. See the DPC Digital Preservation Policy Toolkit for more information.

Understand key disasters, risks, and missed opportunities relating to digital content that has already been identified by colleagues, external audits, customers/users, and other stakeholders:

-

Has there been previous data loss, reputational damage or legal damage due to poor digital preservation practice at your institution?

-

Do stakeholders have live, documented digital preservation concerns that need addressing?

-

Has your institution missed out on a benefit that might be obtained by better investment in digital preservation? What benefits are other institutions able to realise that you cannot?

-

There may also be examples where good digital preservation practice has previously “saved the day”/minimised the impact of an event/protected your organization’s reputation.

Understand current staffing, roles, skills and competencies

Successful digital preservation requires skilled staff and a key component of a business case might be a request for new staff and/or additional training and development opportunities. It is, therefore, important to understand which members of staff currently work on digital preservation activities, where they sit within the organization, what skills they have, and where gaps might exist in terms of both roles and competencies. Which members of staff are within scope will be context dependent but may include: digital preservation practitioners, other information management professionals, IT staff, digital content creators, and more.

The DPC’s Competency Audit Toolkit (DPC CAT) can be used to assess current staffing capabilities within an organization, identifying where gaps exist in relation to current and target digital preservation capabilities as identified during a DPC RAM assessment.

Understand and utilise relevant governance structures

Do you have a steering group or advisory board of relevant stakeholders that can guide digital preservation practice at your organization? Establishing a steering group can provide cross-organizational support, advice and experience of real value to your business case.

Assess the target of your preservation activity: the digital content

Establishing the scope of the digital content to be preserved, which is of relevance to your business case, will be fundamental to understanding requirements and potential solutions.

-

It may be necessary to undertake an audit of current and expected collections within the organization to gather information on the size and nature of the digital content they contain. This information will clarify areas of need and help facilitate decision-making about what should be included within the business case.

-

To help structure this process and gather the information in a reusable format you may wish to capture the information in a Digital Asset Register, if you do not already maintain one. This will then provide a useful tool for both developing the business case and ongoing management of the digital content within your collections. To help gather the information needed, you may wish to use characterisation or content profiling tools to capture data on volumes and types of digital content within the collections. Information on what tools are available can be found on the COPTR tools registry.

-

For content which you do not currently collect, or which does not yet exist, consult with key members of staff (either within your own, or within comparable organizations if possible) to establish well-informed estimates of the size, complexity and challenges of such material. You must be able to justify and defend any figures derived in this way if they are crucial to your business case, so record your sources and your working even if this will not be included in the final business case.

-

The scale and scope of content may well increase over time. Estimates of how volume is likely to change may help to inform a future proof solution.

Identify systems and workflows currently in use

It will be useful to establish the systems and workflows used to create, manage and store the digital content that will be preserved, as well as the systems they interoperate with. This will help you assess current digital preservation capability, gaps in capacity and associated risks. This will be important for identifying potential improvements and solutions and understanding how these solutions fit into the existing system landscape at your organization. This is likely to require conversations with colleagues across several areas, including IT and administrative staff, any third-party solution providers, and potentially external creators and users of digital content.

Understand current practice at other organizations

Gain an understanding of digital preservation capacity and practice at other, similar organizations. This can aid with benchmarking your current capacity as well as helping to set the goals that will be achieved if your business case is funded. It may even be possible to learn lessons from others who have already taken a similar challenge to which your business case seeks to address.

-

There may be particular organizations that your organization typically compares itself with, possibly engaging in peer review or collaboration. These might make useful points of comparison for your business case, particularly if they have already implemented work similar to what you are proposing.

-

If you already have connections with colleagues at similar organizations, you may be able to gather this information through informal conversations. If you wish to make new connections this might be done through membership of networks such as the DPC, the NDSA, or Australasia Preserves or at conferences and events such as iPres, IDCC, or PASIG.

-

DPC members can consult information gathered through a yearly comparison of member RAM assessments - contact your DPC Champion for further information.

Introduction to the Business Case Toolkit

This section provides an overview and introduction to business cases and this toolkit. Use this to find out more about the toolkit and how to apply it.

What is a Business Case and what is it for?

What is a Business Case and what is it for?

Digital preservation within any organization requires investment in people, processes and technology. If an organization would like to change, adapt or expand its digital preservation activities, it is likely that you will need to prepare a business case for further investment in supporting infrastructure, staffing and/or training. A business case will outline the resources required and provide justification for undertaking that investment; evaluating the benefit, cost and risk of alternative options and providing a rationale for a proposed solution.

What is the Digital Preservation Business Case Toolkit?

This Toolkit provides a guide to writing a business case focused on digital preservation activities. While there is no perfect formula for writing a business case (it all depends on what the business case is for, who it is aimed at and how your organization wants you to present it) this toolkit provides a variety of ways to get you thinking about what should go into your business case.

The Toolkit starts with factors to consider when planning your business case, before offering templates and a step-by-step guide to drafting, constructing and delivering your finished case:

-

What makes a good digital preservation business case captures experience pooled from within the DPC on what makes a good policy. Use this to avoid obvious pitfalls and take advantage of approaches that have been successful for other DPC Members.

-

Understand your digital preservation readiness considers what context and preparations are needed before producing a business case. Use this to establish the best foundation for your business case.

-

Step by step guide to building a business case outlines the main steps to follow in constructing your business case including research, drafting, validation and delivery. Use this to plan out how you will develop your proposal.

-

Template for building your business case explores the detail that makes up an evidenced and convincing business case. Use this to guide the development of the content of your proposal.

-

Example benefits and risks for typical digital preservation business cases provides motivations for 4 common business case targets. Use this to develop a strong case for your project.

-

Business case hints and tips provides a summary of helpful ideas on writing business cases and selling your proposal to your organization. Use this to ensure you create a positive and convincing business case.

-

Further resources on business cases provides a list of additional guidance materials relating to business cases.

Who is this toolkit for?

This Toolkit is for anyone who would like to create a business case focused on digital preservation. It is targeted at practitioners (and their managers) who are working with digital resources and would like to obtain funds to expand their digital preservation activities. The Toolkit is primarily aimed at those seeking further funds from within their organization, but could also provide useful information for those writing a bid for project funds from an external funding body.

A great deal of internal advocacy and preparation is often required before you get to the stage of preparing and submitting a business case for a major digital preservation activity, such as establishing a new digital preservation system. For support with pre-business case advocacy activities see the Executive Guide on Digital Preservation and the DPC Rapid Assessment Model.

If your Digital Preservation Business Case has been approved, consult the DPC Procurement Toolkit for advice on the next steps!

Introduction

Providing access to digital content is a core activity for digital preservation practitioners, making up one of the six functional entities of the Reference Model for an Open Archival Information System (OAIS) or ISO 14721:2012. It is widely recognised within the digital preservation community that there is little point in preserving content for the long term if there is not an intention to facilitate access at some point (either now or at a future date), but even providing simpler forms of access to content can be challenge for digital preservation practitioners (as described in Developing an Access Strategy for Born Digital Archival Material), This is particularly the case where large volumes of content and more complex methodologies are employed.

Computational methods of providing access to digital content and metadata are generally considered to be more advanced techniques, certainly a step up from the more standard models of access, for example where a user can browse an online catalogue and view or download one file at a time.

The Levels of Born Digital Access from DLF is a helpful and practical resource which articulates three levels of access under a series of headings, moving from the most simple to the more advanced. Computational access techniques are included at the highest level of the model where the ‘Tools’ section of level 3 states that an organization should “Provide remote access and sophisticated tools for exploring, rendering, and interpretation of data; provide hardware and software to support access to legacy/obscure content, including emulation services.” Examples given within the supporting information include:

-

“Provide open and web-based remote access to materials, including via programming interfaces” and

-

“Provide software for exploring, rendering, and interpreting materials, such as text mining, data visualization, annotation, and natural language processing tools.”

Similarly, the DPC’s Rapid Assessment Model (DPC RAM) puts computational access techniques at the highest level of the model. Level 4 of 'Discovery and access' states that “Advanced resource discovery and access tools are provided, such as faceted searching, data visualization or custom access via APIs”.

There is typically no one-size-fits-all approach to digital preservation and this also extends to access strategies. Organizations are encouraged to weigh up their own priorities, resources and the needs of their users in informing their own approach. So whilst it is acknowledged that not all practitioners will strive for the highest levels of either of these models, many in the community are curious about understanding and exploring these more advanced approaches of access in order to inform their own decision making.

The access strategies of an organization should of course be aligned with the needs of their users. The growing desire for users to be able to carry out their own computational processing on archival metadata for example is mentioned in Born digital archive cataloguing and description. Whilst user needs are not covered in any great detail in our online resource, a helpful introduction can be found in Understanding user needs and it is acknowledged that engaging with users should be a key step in establishing appropriate access strategies.

What is the purpose of this guide?

Computational access is a term mentioned with increasing frequency by those in the digital preservation community. Many practitioners are aware it might be helpful to them (and indeed to their users), but do not have an understanding of what exactly it entails, how it is best applied and, perhaps most importantly, where to start. To add to the challenge, computational access raises professional and ethical concerns. These well-founded but sometimes partially formed concerns, in combination with a lack of practical experience and know-how, mean computational access has been relatively slow to develop within the digital preservation community despite its potential to help with our ambitions to facilitate greater access to digital archives.

The topic was highlighted as a priority by DPC members at the DPC unconference in June 2021. It was clear from discussions that digital preservation practitioners felt this was an area they would like to explore, but one of the key barriers was simply not knowing where to start. This guide has been created to provide an introduction to this topic, and to help the community move forward in applying computational access techniques.

Who is this guide for?

This guide is primarily aimed at digital preservation practitioners with no prior knowledge of computational access. It is a beginner’s guide, intended to provide an overview of key topics as well as tips on getting started and examples of a range of different implementations. It does not hold all the answers, but instead aims to move practitioners towards an understanding of computational access terms and approaches and give them the necessary information and resources to consider whether these techniques could be used to provide access to the digital archives that they hold.

It is not specifically aimed at researchers or users of collections who might want to use computational access techniques to analyze and understand digital collections. Other resources that will help those users are available – see, for example, the Programming Historian and GLAM Workbench. It is important, however, that digital preservation practitioners keep potential users and use cases in mind whilst reading and using this guide

Definitions

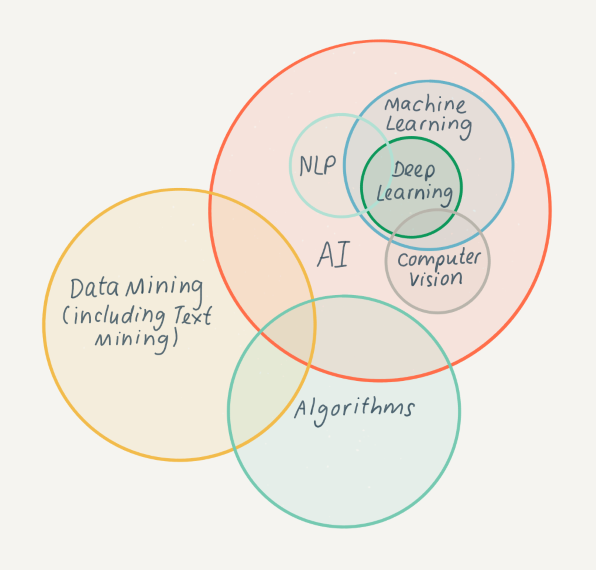

Computational access is often linked with terms such as text mining, machine learning and artificial intelligence, so much so that there is understandable confusion around what each of these concepts entails and where the areas of overlap occur. This section provides clear definitions of key terms and the relationships between them.

Computational Access

The term computational access relates to the ability to enable users to access collections within a digital preservation repository (in a machine-readable manner, e.g., via download or API) in order to analyze, interrogate, or extract new meaning from that material (through, e.g., data or text mining, machine learning) as a means of investigating a particular research question.

This term is first found in the literature in a report by HathiTrust and is closely linked to ‘Collections as Data’ which similarly urges organizations to make their collections available as data, therefore making it possible for users to compute over the material. The term is closely linked to a number of definitions, highlighted in bold above; these and other related terms are discussed below in alphabetical order.

Algorithms

An algorithm is a set of coded instructions normally followed to solve specific problems. A real-world example would be baking a cake; other examples are the process of doing laundry, or the method used to solve a logistic problem.

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been defined by the UK Parliament as:

‘Technologies with the ability to perform tasks that would otherwise require human intelligence, such as visual perception, speech recognition, and language translation.’ They also add that ‘AI systems today usually have the capacity to learn or adapt to new experiences or stimuli.’ AI in the UK: ready, willing and able?

Artificial Intelligence typically takes one specific task, which would normally be done by a human, and provides a method of reliably automating it. An example of this is classifying traffic signs, or recognizing the handwriting of a particular scribe. It especially comes in handy when working with large amounts of material which are extremely time consuming to process manually. Recent developments relating to AI and archival thinking and practice are discussed in the article Archives and AI: An Overview of Current Debates and Future Perspectives.

AI can be split into Broad AI and Narrow AI, and these terms are further defined below.

Broad AI represents a system that is sophisticated and adaptive, able to perform any cognitive task based on its sensory perceptions, previous experience, and learned skills. Currently this type of AI is not achievable due to technical limitations. Read more about steps towards a broad AI.

Narrow AI is task focused. This type of AI is very good at doing one single task, for example, classifying documents into different topics. It is also referred to as Weak AI.

Sometimes Narrow AI becomes so good at a specific task that it can give the impression that it is able to think for itself, so falling under the Broad AI marker. An example of this would be the quick improvement of Voice Assistants, such as Alexa. However, current technology is only able to support Narrow AI.

More information on the differences between these two terms can be found here: Distinguishing between Narrow AI, General AI and Super AI.

Algorithms are a large component of AI, but differ slightly, as AI takes the use of these a step further. AI is basically a set of algorithms that can modify and create new algorithms in response to learned inputs and data, as opposed to relying solely on the inputs it was designed to recognize as triggers.

Computer Vision

Computer vision is a sub domain of AI that focuses on deriving meaningful information from digital images. In an archives context, computer vision could be used to generate metadata for a set of uncatalogued digital images to enable more effective processing, or search and retrieval. A good example of this can be found here: Libraries Use Computer Vision to Explore Photo Archives. As digital images can be of a complicated nature, machine learning is the methodology typically used to carry out this task. You can find out more about computer vision here: What is computer vision?

Data Mining

Data mining is the discipline of finding patterns, correlations, and anomalies in data. A broad range of techniques can be used in data mining, including AI. The data mining workflow can be roughly split into data gathering, data preparation, training, and data analysis. AI is most commonly used during the training stage; this is when the algorithm is trained in a specific task. However, as this discipline mainly focuses on using large amounts of data, AI and algorithms can also be used to aid other steps of the workflow. For example, an algorithm could be written to gather certain information from the web. Find out more about data mining here: Data Mining: What it is & why it matters

Machine Learning

Like computer vision and Natural Language Processing (NLP), machine learning is a sub domain of AI. It differs slightly from computer vision and NLP, as it focuses more on the infrastructure and models than on the techniques and material that are being inputted. Machine learning takes AI to the next level; not only are the algorithms adaptable, but they are also able to perform a task without being explicitly programmed to do so. Find out more about machine learning here: Machine learning. An example of using machine learning on archival collections can be seen on the Archives Hub blog: Machine Learning with Archive Collections.

When talking about AI and machine learning, the terms supervised and unsupervised are sometimes used. These refer to the different approaches that can be taken when applying machine learning. Supervised learning is where a labelled dataset will be used for the algorithm to learn from. A labelled dataset contains items that are tagged (mostly by humans) with an informative label; one example of this is a labelled dataset of images with names of the people who appear in them attached. Unsupervised learning uses a dataset that has not been labelled. This is the biggest difference between these two approaches, but a more nuanced explanation can be found here: Supervised vs. Unsupervised Learning: What’s the Difference?

A term that is also closely linked to machine learning is deep learning. This is a more complex form of machine learning where deep neural networks are used to resemble the complex structure of the human brain. Read more about the differences between deep learning and machine learning here: Deep Learning vs. Machine Learning – What’s The Difference?

Natural Language Processing (NLP)

NLP, just like computer vision and machine learning, is another sub domain of AI. This sub domain focuses on the ability of a computer program to understand human language as it is spoken and written. You can read more about NLP here: Natural Language Processing (NLP). Most of the time, due to the complexity of human language, machine learning will be used alongside NLP to produce better results. An example of this is text classification, where due to the ambiguous and unstructured nature of human language, this approach has only been able to evolve since the use of machine learning.

Text Mining

Text mining is very similar to data mining, the biggest difference being that instead of collecting data in general, text mining focuses solely on collecting text. Therefore, while text mining is data mining, data mining is not necessarily text mining. Text mining typically results in a large quantity of unstructured text which is difficult to analyze, so more advanced methods such as machine learning are often used in association with it to help make sense of the resulting dataset. Read more about text mining and its relationship to machine learning and NLP here: What is Text Mining, Text Analytics and Natural Language Processing?

As is apparent from the definitions as described above, there are close relationships between many of the terms used. The diagram below illustrates some of these areas of overlap.

Subcategories

Template for building a Business Case

This section provides guidance on the content that will be useful to include in your business case, but it will likely need to be adapted to the structure used in your organization’s template.