Creators and publishers of digital resources, third-party service providers, operational managers (DigCurV Manager Lens) and staff (DigCurV Practitioner Lens) with responsibility for implementing institutional activities of relevance to digital preservation. It is assumed that these will include a) staff from structurally separate parts of the organisation, and b) a wide range of knowledge of digital preservation, from novice to sophisticated; c) both technical and non technical perspectives; d) a wide range of functional activities with a direct or indirect link to digital preservation activities.

Wide-ranging, from novice to advanced.

Download a PDF of this section.

Any change in the economic environment may mean that many organisations are challenged to reduce overall expenditure and to maximise efficiencies. At the same time organisations are preserving increasing amounts of digital material. Reuse of models can form a part of the response to this challenge. The long term management - preservation - of digital materials is an expensive and complex activity. It cannot reliably be done without the investment of resources and expenditure.

The challenges for an organisation are to create business models that:

Other organisations have already created templates for business cases and models for the calculation of cost and benefit, so reusing some or parts of these models can not only save time but be used as justification for the adoption of particular strategies.

The business case is a tool for advocating and ensuring that an investment is justified in terms of the strategic direction of the organisation and the benefits it will deliver. It typically provides context, benefits, costs and a set of options for key decision makers and funders. It can also set out how success will be measured to ensure that promised improvements are delivered.

It is essential that any business model or proposal that is created supports the wider aims and objectives of the parent organisation. It is equally important that key stakeholders, such as budget holders, are consulted and given early sight of the plans and offered the opportunity to comment and provide input. Early exposure of plans can to some extent mitigate situations in which plans might otherwise be rejected outright.

However, presenting a business case for preserving any material at an early stage is no guarantee that it will be accepted. Whilst there is no sure fire template, some or all of the following steps may be useful if a plan is rejected. Within an organisation there may be set procedures and policies regarding the making and presentation of business cases and these should be followed. Early communication of business planning can help identify topics or areas that could present problems when the plan is formally presented.

The point of business planning is to be aspirational and to create services or products that have value and benefit. Not everyone sees the benefits in preservation over the long term where costs are an ongoing issue or where resources are required to be committed for the long term. Business planning is often an exercise in pragmatism. It might be more effective to make a number of smaller more focussed business plans than one single large proposal. Using their knowledge of an organisation the author of a business plan must ensure that any plan is realistic and within the means of the organisation. Strategic planning provides the framework within which business plans are written. Any strategic objective can be achieved in a number of ways, e.g. less money but more time, fewer staff but longer timeframe etc. A pragmatic response offers decision makers a preferred option and why it is preferred and a small range of other alternative options in the business case. It is often helpful to include the "costs/dis-benefits of inaction" as an option against which other actions can be evaluated.

Work with stakeholders to identify reasons why a business plan was rejected. Talk to those involved in decision making and seek specific feedback. Was the cost component too expensive? Were the plans too ambitious? Is it felt the business case was poorly written or presented? Does the timeframe not fit with organisational plans?

Response: Work with stakeholders to address key concerns. Be clear to address each issue. Explain the reasons why a business plan was presented and what it is aiming to achieve. Focus on benefits, especially those that address the key strategic goals of the parent organisation. Focus on short as well as longer term benefits of the business plan. One approach is to create business plans that are 'SMART', that is Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Timely.

The hard work in business planning is getting to the point where a plan is accepted. However, circumstances can change. If a business plan is not implemented or previously agreed funding withdrawn, the implications can be severe. Again, communication with key stakeholders is essential and can reveal why something may have changed.

Response: Part of business planning involves having a range of options that can be offered in the event of problems arising with funding a preferred option. Having a well-structured business plan from which proposals can be deleted can help in making an alternative case for phased or alternative implementations requiring fewer resources. In such a case a business plan might quickly be re-drafted in more acceptable terms and resources made available. Having a focus on why resources were not made available gives an opportunity for a business case to be re-presented with more emphasis on benefits and positive impact.

The following steps should be considered when writing and delivering a business case.

Creating a business case |

|

1. Audit your digital materials and prioritise work required |

Audit your digital materials. Analyse the risks and opportunities for your digital materials. Use your analysis to prioritise areas of work and assign owners to them. |

2. Is this the right time? |

What are you already doing? Is it the right time to do new things on your own? Can you collaborate with others? |

3. Institutional analysis |

How ready is your institution for change in terms of content and process? |

4. Stakeholder analysis and advocacy |

Who will be working on and using the digital materials? Who decides on funding? Engage with them using language and terms they will understand. |

5. Objectives: scope aims, activities, plan and costs |

Map out what are you going to do, who will do what, what will it cost, and when it will happen. |

6. Map benefits to organisational strategy |

Make sure you express the benefits of your business case in a way that your funders will understand. |

7. What else is needed? |

Do you need to include a cost-benefits analysis or list of options based on expenditure and outcome? |

8. Validate and refine business case |

Review and test your business case against best practice and identify what else it needs. |

9. Deliver the business case with maximum impact |

Do you have a champion to use in the organisation? Remember you may need to deliver it again. |

10. Share an edited business case |

Remove confidential material and share online so others can benefit from your work |

For a generic digital preservation business case template and more information, see the Digital Preservation Business Case Toolkit

Benefits are associated with costs and also with risks (see Risk and change management). If risks are mitigated these become a type of benefit. The purpose of the acquisition of any digital material is that it is used. The uses to which digital material is put represents a benefit to those users. If an organisation needs to understand costs associated with digital materials then it must also understand benefits. Benefits can be used to justify costs through the development of business plans.

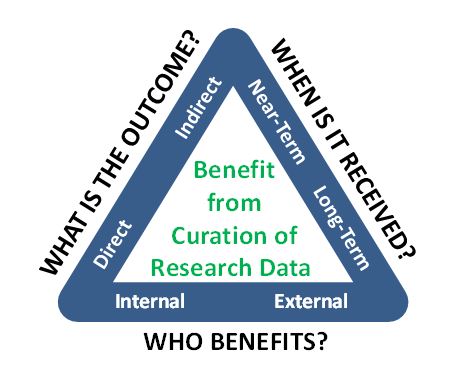

Measuring benefits is often quite challenging, especially when these benefits do not easily lend themselves to expression in quantitative terms. Often a mixture of approaches will be required to analyse both qualitative and quantitative outcomes and present the differences made. To assist institutions, the Keeping Research Data Safe project created a KRDS Benefits Framework and a Benefits Analysis Toolkit (KRDS, 2011). These aim to help institutions identify the full scope of benefits from management and preservation of research data and to present them in a succinct way to a range of different stakeholders (e.g. when developing business cases or advocacy). The toolkit is also easily applicable to the benefits of digital preservation to other classes of digital materials.

The KRDS Benefits Framework uses three dimensions to illuminate the benefits investments potentially generate. These dimensions serve as a high-level framework within which thinking about benefits can be organised and then sharpened into more focused value propositions using the Toolkit. It helps you identify what changes you are trying to deliver, what are the outcomes, who benefits, and how long it will take to realise those benefits.

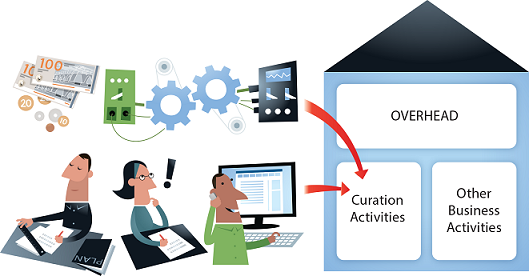

A business case will normally look at not just the establishment cost for the digital preservation solution, but the all-in cost, including project/program management costs and other activities being undertaken to support implementation such as training and publicity. However digital preservation costs are often the most critical element.

These are a few reasons why an organisation might want to estimate digital preservation costs:

A number of research and development projects have sought to model digital preservation costs across the lifecycle from creation and ingest through to preservation and ultimately access. The large number of projects makes understanding this work, finding which results are most applicable to a particular situation, choosing a model, and putting it into practice a significant challenge. The 4C Project surveyed, analysed and assessed this work and provides guidance on getting the most from it:

Cost modelling has been identified as a particularly challenging activity, with a number of difficult aspects, such as:

For this reason, modelling digital preservation costs across the lifecycle is an activity that should be approached with caution. Cost modelling will always be an approximation and so you need to decide the amount of time you are willing to put in to gain a less approximate answer.

It is possible to manage costs through careful planning. One way is through good process design. The ways in which digital material is created or acquired, managed and disseminated attract costs. Those costs are at the discretion of the organisation and can be managed. The end to end process from acquisition to dissemination must be designed to ensure that all activities are as efficient as possible. All steps should be designed in such a way as to minimise the need for resources, whilst maximising efficiency. Whilst efficiencies work well at scale, an efficient process doesn't have to be a high volume process. Automation of systematic steps can also save time and deliver effective consistent processes. The initial costs of process design and implementation can be offset by longer term returns.

Impact is typically the measurement of benefits particularly to the wider public and society undertaken after a business case project has delivered.

For small projects and business cases, impact may be just a simple set of measures such as downloads or number of website requests against which success can be benchmarked easily.

For larger projects and programmes, it may be part of a more thorough evaluation to justify the resources expended. It can include a mixture of quantitative and qualitative measures and will normally be undertaken by external specialists working with staff from the repository. They employ methods from economics and management and information science, for example cost-benefit analysis or contingent valuation, and traditional social science methods such as interviews, surveys and focus groups.

Measurement involves choosing metrics or indicators and requires careful planning and agreement about what to measure and how. Metrics often employ readily countable things such as downloads, or scales metrics that are not truly numeric, such as rating scales or categories of variables. Typically there is a trade-off between what ideally should be measured (e.g. users and use) and proxy measures which are easy to capture and measure (e.g." unique visitors" and web downloads).

Sustainable Economics for a Digital Planet: Ensuring Long-Term Access to Digital Information

http://brtf.sdsc.edu/biblio/BRTF_Final_Report.pdf

The Blue Ribbon Task Force investigated sustainable digital preservation and access from an economic perspective. This final report, identifies problems intrinsic to all preserved digital materials, and proposes actions that stakeholders can take to meet these challenges to sustainability. It developed action agendas that are targeted to major stakeholder groups and to domain-specific preservation strategies. (2010, 116 pages).

This synthesis summarises and reflects on the combined findings from a series of independent investigations into the value and impact of three well established UK research data centres or services (the Economic and Social Data Service, the Archaeology Data Service, and the British Atmospheric Data Centre). The studies adopted a number of approaches to explore the value and impacts of research data services and the data sharing and archiving that they have enabled. Data collection involved focused user and depositor surveys, and data centre financial and operational data (e.g. user registrations, dataset deposits and downloads), supplemented by in-depth interviews. Not all impacts can be captured and quantified; therefore they have used these economic approaches with others, such as the KRDS Benefits Framework, to illustrate wider benefits. (2014, 26 pages).

https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/digitising-your-collections-sustainably

Provides a starting point for considering the issues necessary to create and build a business model that will support sustainability of digitisation and digital collections.

The European Union funded 4C project aimed to help organisations across Europe to invest more effectively in digital curation and preservation. A series of reports and resources were produced and are available from its outputs and deliverables page. These include the Digital Curation Sustainability Model , an Evaluation of Cost Models and Needs & Gaps Analysis, a Report on Risk, Benefit, Impact and Value, and a Draft Economic Sustainability Reference Model. The evaluation of costs models report evaluates ten available cost models including, KRDS and LIFE. Another major output was the Curation Costs Exchange (CCEx), a community owned platform which helps organisations of any kind assess the costs of curation practices through comparison and analysis. The CCEx aims to provide real information about costs to help make more informed investments in digital curation. The CCEx was launched in 2014 by 4C and is now maintained and governed by the Digital Preservation Coalition (DPC) with help from nestor and The Netherlands Coalition for Digital Preservation (NCDD).

http://wiki.dpconline.org/index.php?title=Digital_Preservation_Business_Case_Toolkit

This Toolkit provides an in depth guide to writing a business case that is focused on digital preservation activities. It's targeted at practitioners (and their managers) who are working with digital resources and would like to obtain funds to expand their digital preservation activities. The Toolkit is primarily aimed at those seeking further funds from within their organisation, but could also provide useful information for those writing a bid for project funds from an external funding body. It includes a Step by step guide to building a business case and a Template for building a business case. Created by the Jisc funded SPRUCE Project in 2013 the toolkit wiki is hosted by the DPC.

Keeping Research Data Safe (KRDS) is a series of cost/benefit studies, tools and methodologies that focus on the challenges of assessing costs and benefits of curation and preservation of research data. Although focussing on research data, the tools are easily customised to apply to other areas of digital preservation. Available outputs include a KRDS Factsheet, a KRDS User Guide, a KRDS Activity Cost Model, and a KRDS Benefits Analysis Toolkit as well as supplementary materials and reports. The KRDS projects between 2008 and 2011 were funded by Jisc.

http://www.metaarchive.org/public/publishing/ma_20costquestions_final.pdf?thumblink

The MetaArchive Cooperative has produced a set of 20 questions to "assist institutions with their comparative analysis of various digital preservation solutions". This work marks a move away from the development of detailed predictive costing models towards a more general approach that seeks to identify and understand key cost drivers rather than the actual costs themselves.

http://blog.dshr.org/search/label/storage%20costs

http://blog.dshr.org/search/label/cloud%20economics

David Rosenthal is a frequent blogger on the topic of storage costs, often considering the impact of the evolution of storage technology on preservation costs and on cloud storage.

A bibliography that "ranges broadly, from articles on "contingent valuation," "ecosystem valuation" and the general "costs" of knowledge, to those that directly address the cost issues associated with digital preservation and stewardship".

http://wiki.opf-labs.org/display/CDP/Home

A list of digital preservation cost models and cost modelling initiatives.

![]()

https://coi.weareavp.com/rationale

This is a great information video from AVPreserv on the cost of inaction and the business case rationale for digital preservation. It is focussed on Audio-Visual material but it worth listening to and thinking laterally about the underlying rationale whatever type of digital material you hold. (8mins 41sec)

![]()

There are 4 case studies providing worked examples of completed worksheets from project partners as follows:

Archaeology

The background to this case study is provided in the Archaeology Data Service (ADS) dissemination workshop presentation. Worked examples are available of the ADS Benefits Framework Worksheet (PDF) and the ADS Value-chain and Impact Worksheet (Excel 97-2003).

Health: Population Cohort Studies

http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/events/i2s2-krds/presentations/dipak-kalra-krds-benefits-2011-07.ppt

The background to this case study is provided in the Medical Research Council Cohort Studies dissemination workshop presentation. A worked example is available of the Cohort Studies Value-chain and Impact Worksheet (Excel 97-2003).

Research Data Citation: SageCite

http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/events/i2s2-krds/presentations/monica-duke-krds-sagecite-benefits-2011-07.ppt

The background to this case study is provided in the SageCite dissemination workshop presentation. A worked example is available of the SageCite Benefits Framework Worksheet (PDF).

Social Sciences: UK Data Archive (UKDA)

http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/events/i2s2-krds/presentations/matthew-woollard-krds-benefits-2011-07.ppt

The background to this case study is provided in the UKDA dissemination workshop presentation. A worked example is available of the UKDA Benefits Impact Worksheet (PDF).

There are four case studies as follows sourced from activities conducted as part of SPRUCE Project Awards:

Bishopsgate library case study

http://wiki.dpconline.org/index.php?title=Bishopsgate_library_case_study

A collections audit and business case focused on taking the first steps of digital preservation.

Institute of education case study

http://wiki.dpconline.org/index.php?title=Institute_of_education_case_study

A review of approach and generation of a business case for digital administrative record keeping.

Northumberland estates case study

http://wiki.dpconline.org/index.php?title=Northumberland_estates_case_study

Assessment of digital repository solutions and an associated business case for digital preservation.

Lovebytes case study

http://wiki.dpconline.org/index.php?title=Lovebytes_case_study

A trial of media stabilisation and content preservation along with a business case to move to a production status.

Keeping Research Data Safe (KRDS), 2011. Digital Preservation Benefits Analysis Toolkit. Available: http://beagrie.com/krds-i2s2.php

The use and development of reliable standards has long been a cornerstone of the information industry. They facilitate the access, discovery and sharing of digital resources, as well as their long-term preservation. There are both generic standards applicable to all sectors that can support digital preservation, and industry-specific standards that may need to be adhered to. Using standards that are relevant to the digital institutional environment helps with organisational compliance and interoperability between diverse systems within and beyond the sector. Adherence to standards also enables organisations to be audited and certified.

There are a number of standards which can help with the development of an operational model for digital preservation.

Taking custodial control of digital materials requires a set of procedures to govern their transfer into a digital preservation environment. This can include identifying and quantifying the materials to be transferred, assessing the costs of preserving them and identifying the requirements for future authentication and confidentiality. ISO 20652: Space Data and Information Transfer Systems - Producer-Archive Interface - Methodology Abstract Standard (ISO, 2006) is an international standard that provides a methodological framework for developing procedures for the formal transfer of digital materials from the creator into the digital preservation environment. Objectives, actions and the expected results are identified for four phases - initial negotiations with the creator (Preliminary Phase), defining requirements (Formal Definition Phase), the transfer of digital materials to the digital preservation environment (Transfer Phase) and ensuring the digital materials and their accompanying metadata conform to what was agreed (Validation Phase).

ISO 14721:2012 Space Data and Information Transfer Systems - Open Archival Information System - Reference Model (OAIS) (ISO, 2012b) provides a systematic framework for understanding and implementing the archival concepts needed for long-term digital information preservation and access, and for describing and comparing architectures and operations of existing and future archives. It describes roles, processes and methods for long-term preservation. Developed by the Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems (CCSDS) OAIS was first published in 1999 and has had an influence upon many digital preservation developments since the early 2000s. A useful introductory guide to the standard is available as a DPC Technology Watch Report (Lavoie, 2014).

An OAIS is ‘an archive, consisting of an organization of people and systems that has accepted the responsibility to preserve information and make it available for a defined ‘Designated Community’. An ‘OAIS archive’ could be distinguished from other uses of the term ‘archive’ by the way that it accepts and responds to a series of specific responsibilities. OAIS defines these responsibilities as:

OAIS also defines the information model that needs to be adopted. This includes not only the digital material but also any metadata used to describe or manage the material and any other supporting information called Representation Information.

The OAIS functional model is widely used to establish workflows and technical implementations. It defines a broad range of digital preservation functions including ingest, access, archival storage, preservation planning, data management and administration. These provide a common set of concepts and definitions that can assist discussion across sectors and professional groups and facilitate the specification of archives and digital preservation systems.

OAIS provides a high level framework and a useful shared language for digital preservation but for many years the concept of ‘OAIS conformance/compliance’ remained hard to pin down. Though the term was frequently used in the years immediately following the publication of the standard, it relied on the ability to measure up to just six mandatory but high level responsibilities. A more detailed discussion about ‘OAIS compliance’ can be found in the Technology Watch Report.

ISO/TR 18492:2005 Long-term preservation of electronic document-based information (ISO/TR, 2005) provides a practical methodology for the continued preservation and retrieval of authentic electronic document-based information, which includes technology-neutral guidance on media renewal, migration, quality, security and environmental control. The guidance is developed to ensure authenticity of records beyond the lifetime of original information keeping systems.

ISO 15489:2001 Information and documentation -- Records management (ISO, 2001) can also be a useful standard for defining the roles, processes and methods for a digital preservation implementation where the focus is the long-term management of records. This standard outlines a framework of best practice for managing business records to ensure that they are curated and documented throughout their lifecycle while remaining authoritative and accessible.

ISO 16175:2011 Principles and functional requirements for records in electronic office environments (ISO, 2011) relates to electronic document and records management systems as well as enterprise content management systems. While it does not include specific requirements for digital preservation, it does acknowledge the need to maintain records over time and that format obsolescence issues need to be considered in the specification of these electronic systems.

There are international standards that are generic to good business management that may also be relevant in the digital preservation domain.

There are a number of routes through which a digital preservation implementation can be certified. These range from light touch peer review certification methods such as the Data Seal of Approval, through the more extensive internal methods of DIN 31644 Information and documentation - Criteria for trustworthy digital archives (DIN, 2012), to the comprehensive international standard ISO 16363:2012 Audit and certification of trustworthy digital repositories (ISO, 2012a) (see Audit and certification).

There are specific advantages to using standards for the technical aspects of a digital preservation programme, primarily in relation to metadata and file formats.

In conjunction with relevant descriptive metadata standards, PREMIS and METS are de facto standards which will enhance a digital preservation programme. PREMIS (PREservation Metadata: Implementation Strategies) is a standard hosted by the Library of Congress and first published in 2005. The data dictionary and supporting tools have been specifically developed to support the preservation of digital material. METS (Metadata Encoding and Transmission Standard) is an XML encoding standard which enables digital materials to be packaged with archival information (see Metadata and documentation).

There are also standards relating to file formats. Choosing file formats that are non-proprietary and based on open format standards gives an organisation a good basis for a digital preservation programme. ISO/IEC 26300-1:2015 Open Document Format for Office Applications (ISO/IEC, 2015) provides an XML schema for the preservation of widely used documents such as text documents, spreadsheets, presentations. ISO 19005 Electronic document file format for long-term preservation (ISO, 2005) prescribes elements of valid PDF/A which ensures that they are self-contained and display consistently across different devices. Aspects of JPEG-2000 and TIFF are also covered by ISO standards. (see File formats and standards).

A standards based approach to digital preservation is important, but there are also factors which inhibit their use as a digital preservation strategy:

These factors mean that standards will need to be seen as part of a suite of preservation strategies rather than the key strategy itself. The digital environment is not inclined to be constrained by rigid rules and a digital preservation programme can often be a blend of standards and best practice that is sufficiently flexible and adapted to suit the needs of the organisation, its circumstances and the digital materials being managed.

In recent years best practice guidance and case studies have been published by national archives, national libraries and other cultural organisations. Digital preservation is also a topic well discussed on blogs and social media which can often provide real time information in relation to theory and practice from around the world. Papers at conferences such as iPRES, the International Digital Curation Conference (IDCC) and the Preservation and Archiving Special Interest Group (PASIG) can be a useful source of up to date thinking from academics and practitioners in digital preservation.

Standards should be understood as a formal description and recognition of what a community of experts might term best practice. Standards, and the best practice from which they derive can be intimidating and there is a risk for those starting in digital preservation that the ‘best becomes the enemy of the good’. So in adopting or recommending standards it should always be understood that some action is almost always better than no action. Digital preservation is a messy business which throws up unexpected challenges. So it is almost always the case that a poorly implemented standard is preferable to waiting for perfection.

Specific industries have become active in the development of preservation standards, and particular types of content and use cases have emerged that overlap and extend a number of standards. There is considerable benefit in digital preservation standards being embedded in sector-specific standards since this will greatly assist their adoption, although this may present a challenge to coordination of activities. Three examples are given below:

![]()

http://jennriley.com/metadatamap/

The sheer number of metadata standards in the cultural heritage sector is overwhelming, and their inter-relationships further complicate the situation. This visual map of the metadata landscape is intended to assist planners with the selection and implementation of metadata standards. Each of the 105 standards listed here is evaluated on its strength of application to defined categories in each of four axes: community, domain, function, and purpose. (2010, 1 page).

Dlib Magazine publishes on a regular basis a wide range of papers and case studies on the practical implementation of digital preservation standards and best practice. ![]()

https://www.coretrustseal.org/

http://www.loc.gov/standards/premis/

Library of Congress, 2015

The Digital Curation Centre makes available research and case studies in relation to the preservation of research data. Iit also publishes recordings of its annual international digital curation conference proceedings.

http://blogs.loc.gov/digitalpreservation/

The Signal is a digital preservation blog published by the Library of Congress

http://www.ipres-conference.org/

IPRES, the International Conference on Digital Preservation publishes a website and proceedings from their annual event which looks at different themes within the digital preservation landscape,

http://wiki.dpconline.org/index.php?title=Main_Page

The Digital Preservation Coalition Wiki provides a collaborative space for users of OAIS, the British Library’s file format assessments as well as other resources.

http://preservationmatters.blogspot.co.uk/

The Digital Preservation Matters blog is a personal account of experiences from working with Digital Preservation

DIN, 2012. DIN 31644 Information and documentation - Criteria for trustworthy digital archives. Available: http://data-archive.ac.uk/curate/trusted-digital-repositories/standards-of-trust?index=3

IASA-TC04, 2009. Guidelines in the Production and Preservation of Digital Audio Objects: standards, recommended practices, and strategies: 2nd edition, edited by Kevin Bradley. Available: http://www.iasa-web.org/tc04/publication-information

ISO, 2001. ISO 15489:2001 Information and documentation -- Records management. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=31908

ISO, 2005. ISO 19005-1:2005. Document management -- Electronic document file format for long-term preservation. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=38920

ISO, 2006. ISO 20652:2006 Space Data and Information Transfer Systems - Producer-Archive Interface - Methodology Abstract Standard. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=39577

ISO, 2011. ISO 16175:2011 Principles and functional requirements for records in electronic office environments. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=55791

ISO, 2012a. ISO 16363:2012 Audit and certification of trustworthy digital repositories. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=56510

ISO, 2012b. ISO 14721:2012 Space Data and Information Transfer Systems - Open Archival Information System (OAIS) - Reference Model. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=57284

ISO, 2015. ISO 9001:2015 Quality management systems. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=62085

ISO/IEC, 2009. ISO/IEC 15408:2009 The Common Criteria for Information Technology Security Evaluation. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=50341

ISO/IEC, 2013. ISO/IEC 27001:2013 Information technology -- Security techniques -- Information security management systems. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=54534

ISO/IEC, 2015. ISO/IEC 26300-1:2015 Information technology -- Open Document Format for Office Applications (OpenDocument) v1.2 -- Part 1: OpenDocument Schema. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available:http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_ics/catalogue_detail_ics.htm?csnumber=66363

ISO/TR, 2005. ISO/TR 18492:2005 Long-term preservation of electronic document-based information. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=38716

Lavoie, B., 2014. The Open Archival Information System (OAIS) Reference Model: Introductory Guide (2nd Edition). DPC Technology Watch Report 14-02. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.7207/twr14-02

Library of Congress, 2015. METS Metadata Encoding and Transmission Standard. Available: http://www.loc.gov/standards/mets/

A well-skilled and effective workforce can be an organisation's greatest asset, yet due care and attention is not always given to providing adequate training and development, and encouraging its uptake. Additionally, developing and maintaining a digital preservation programme can seem daunting in many ways and, in particular, this is often due to a perceived staff skills gap. This may be because the work environment is characterised by:

Carefully designed staff training and continuous professional development (CPD) activities can play a key role in successfully making the transition from the traditional model of libraries and archives to the digital or hybrid model. Intelligent training and development can do much to boost confidence and ability in staff members, and minimise anxiety about the changing nature of work in preservation-performing institutions. A thoughtful approach to training and development (as opposed to just "sending people on courses") is likely to make a significant difference by:

Organisations should take a strategic approach to training and development, considering carefully the skills that are required, as well as new and developing roles and responsibilities. The issue should be clearly addressed in all relevant digital preservation policy, strategy and planning, and budget for advocacy and skills development activities should be an integral part of planning for digital preservation work.

Successful digital preservation work requires a broad range of skills, from those specific to the area such as knowledge of metadata standards and audit frameworks, to more general skills such a project planning and risk management. Therefore, ensuring all staff members have adequate digital preservation-specific skills for their part of the process is only one aspect of the preparation required for equipping them to maximise the potential of digital technology. It is highly unlikely that one individual will ever possess all of the skills required to undertake the full range of digital preservation activities, so collaboration will remain key to success. Skilful training can enhance individual skills and competences but can also enhance understanding of the other skills and competences required for a successful collaborative project.

A number of different initiatives have endeavoured to clarify the skills and competencies required for digital preservation work and potential roles involved for staff at different levels of seniority:

The Library of Congress's Digital Preservation Outreach and Education programme (DPOE) has defined three levels of staff roles (or career stages) within their model for digital preservation training. These are:

The DigCurV project adapted the DPOE's three level model for their work in defining the core competencies required for digital preservation work. The DigCurV project examined a number of issues relating to digital curation and preservation training, skills and development, producing a variety of useful resources including a database of available training opportunities and a curriculum framework. Describing the core competencies required at each of the three levels in the DPOE model through a set of 'lenses', the DigCurV curriculum framework provides an excellent resource for those looking to identify the full range of skills and competencies required for digital curation and preservation. Specifically, the DigCurV curriculum framework can help users to describe and compare training courses, to develop new training resources and to map the skills and knowledge of an individual or team to identify any existing skills gaps.

Each lens is split into four sections covering

Each then contain further sub-sections that list general statements about individual competencies. The statements are designed to be generic so have a broad applicability, although specific examples of particular standards or tools relating to the competencies are available via the version on the DigCurV website.

The DigCCurr (Preserving Access to Our Digital Future: Building an International Digital Curation Curriculum) project has produced a 6-dimensional matrix for identifying and organizing the material to be covered in a digital curation curriculum. This Matrix of Digital Curation Knowledge and Competencies is an alternative approach that may be particularly useful for smaller organisations.

Roles and responsibilities need to be clearly defined. The success of training and development programmes will be affected by the degree to which various roles and responsibilities mesh. It is essential that each of the stakeholders in the process fully appreciate their roles and actively participate in the process. Listed below is a guide to the various responsibilities that may be required of different stakeholders to ensure the creation and deployment of a successful and comprehensive training and development programme.

Stakeholder roles and responsibilities |

Roles and Responsibilities of the Institution

|

Roles and Responsibilities of Professional Associations

|

Roles and Responsibilities of the Individual

|

A useful starting point for any organisation is to conduct a skills audit tailored to the needs of the specific institution. The process will help identify any skills gaps that exist and allow informed decisions to be made about training and development, as well as potentially highlighting additional roles that may require new staff or new responsibilities (and new job descriptions) for those already in post. Evidence from the skills audit can then be used to build a business case for any additional resources that may be required. In addition to being an excellent starting point for improving staff development it may also be useful to incorporate elements of the process into regular staff professional development and review processes.

The DigCurV curriculum framework or the Matrix of Digital Curation Knowledge and Competencies can provide a useful tool when carrying out a skills audit, in this case as a resource for benchmarking. It will be necessary to tailor the audit to the staff development practices and processes of individual organisations but the following steps may be considered:

A lack of established training and development opportunities was previously a considerable barrier to those wishing to learn more about digital preservation. While those at more advanced levels in their development may still struggle to find appropriate opportunities, there are now a number of established courses available to those at a beginner and intermediate level from short courses to full degree programmes including a variety of training opportunities addressing specific specialist areas of interest. A greater barrier is now the time and expense involved in attending face-to-face training, but increasingly more online and distance learning options are being made available so this impediment will also decrease.

Digital preservation courses have also previously suffered from criticism relating to an emphasis on theory rather than practice. This too is changing with more practical exercises and tool demos being incorporated into training. Digital preservation also remains a discipline where as much, if not more, can be learnt by doing, so peer to peer learning and a willingness to just get your hands dirty can often produce the best results. Information sharing and short staff exchanges with similar organisations can provide a particularly effect method for staff development and learning.

![]()

http://www.digitalpreservation.gov/education/2014_Survey_Report-Final.pdf

An analysis of the state of digital preservation practice and the capacity to preserve digital content within organisations in the United States with the aim of establishing training gaps and needs. (13 pages).

![]()

The DigCurV Curriculum Framework offers a means to identify, evaluate, and plan training to meet the skill requirements of staff engaged in digital curation. The DigCurV team undertook multi-national research in the Cultural Heritage sector to understand the skills used by those working in digital curation, and those sought by employers in this sector. The framework defines separate skills lenses to match the specific needs of three distinct audiences; Executives, Managers, and Practitioners.

http://ils.unc.edu/digccurr/digccurr-matrix.html

The DigCCurr (Preserving Access to Our Digital Future: Building an International Digital Curation Curriculum) project has produced a 6-dimensional matrix for identifying and organizing the material to be covered in a digital curation curriculum.

http://www.digitalpreservation.gov/education/curriculum.html

The Library of Congress's 'baseline' digital preservation training programme for archives and collections management staff. The full course is delivered to archives and other digital preservation professionals in a 'train the trainer' approach, in order to support further dissemination to colleagues. The overview videos are available online.

https://www.dpconline.org/knowledge-base/training

A key role for the DPC is to empower and develop its members' workforces. The DPC addresses this issue by facilitating training and support activities and creating practitioner-focused material and events throughout each year. These include The DPC Leadership Programme, The Digital Preservation Roadshow, and The Member Briefing Days and Invitational Events.

A range of UK based digital preservation training courses. Scheduled DPTP courses run over 2 days or 3 days and take place regularly throughout the year.

An excellent free online tutorial that introduces you to the basic tenets of digital preservation. It is particularly geared toward librarians, archivists, curators, managers, and technical specialists. It includes definitions, key concepts, practical advice, exercises, and up-to-date references. The tutorial is available in English, French, and Italian.

http://www.dpconline.org/knowledge-base/training

The DPC maintains a list that will be helpful to anyone looking at post- graduate degrees with a focus on digital preservation. It includes University on campus and distance learning options. Some universities also offer individual credit bearing modules in relevant digital preservation topics.

http://www.arsc-audio.org/etresources.html

Training opportunities in Australia, Europe and the USA for those working with sound and moving image material.

http://www.connectingtocollections.org/av/

Self-paced course including recorded webinars, hand-outs, slideshows and suggested further reading for the individual student working with audio-visual material. It covers basic principles, a history of formats and their preservation challenges, format identification, access issues and an overview of existing models and standards. It is written in English by a team of US-based archivists, conservators and digital preservation experts.

![]()

Short interviews with 5 candidates who were sponsored by the Digital Preservation Coalition to attend the Digital Futures Academy in London in March 2012. They reflect on their experience and how joining the DPC has benefitted their institutions. (2 mins 40 secs)

Digital preservation is not simply about risks. It also creates opportunities and by protecting digital materials it means that new or extended value can be derived from them. It can be easy to become overwhelmed with risks, so It is worth being explicit early in the process about what opportunities are being protected or created. There are many things that put your digital resources at risk including changes to your organisation or technology. If not managed, these risks will have a significant impact on your ability to carry out your digital preservation activities, wider business functions, or comply with legislation.

To manage digital preservation, you must understand your organisation's specific issues and risks. You can do this by undertaking a risk and opportunities assessment. The assessment will highlight specific risks to the continuity of your digital resources, and opportunities that can be realised from mitigating these risks.

Experience shows that the risks facing digital resources are subtle and varied. They include, but are not limited to the following:

|

|

Data loss is likely to have a variety of real world consequences depending on context. In the context of a court case, for example, the authenticity of a document could become a significant legal issue; whereas for highly structured research data the chain of custody may matter less than access to explanatory context that enables the reproducibility of an experiment. In many contexts it may be technically possible to recover digital collections but where an organisation simply doesn't have the wherewithal or skills necessary to restore a data set, then practical obsolescence and data loss can result. This is likely to become more of a reality as the number and complexity of digital collections expand.

The risks to digital content usually matter because of their consequences in the real world. Again this depends on the context but the following can occur:

Risks are typically prioritised by calculating a 'risk score' based on likelihood, impact and imminence: an imminent risk with a strong probability and a large negative impact needs prompt action. Depending on the nature of the risk this might include taking steps to reduce the likelihood of a risk emerging, reducing the impact if a risk does occur, or buying time for mitigation steps to be implemented.

Risk assessment is an ongoing process that can be developed and expanded through time. It can help bring together different stakeholders and, because risk management is understood by senior management it can also help to make the case for investment. Even an elementary risk assessment will highlight priorities for anyone getting started in digital preservation.

Finally it is worth noting that digital preservation is distinctive in being long-term and most risk methodologies are typically focussed on the short-term. For digital preservation, you need to be aware that over the long term improbable events will become more likely and special attention should be paid to those with significant consequences.

'Interested parties and stakeholders require that organizations proactively prepare for potential incidents and disruptions in order to avoid suspension of critical operations and services, or if operations and services are disrupted, that they resume operations and services as rapidly as required by those who depend on them.' (ISO/PAS 22399:2007).

Business Continuity planning and practice is well-established within the IT profession and is not dealt with in detail in the Handbook. However it is an important component of ensuring bit preservation and makes a significant contribution to digital preservation through this. There is a series of webinars on business continuity and digital preservation from the TIMBUS project (see Resources).

The development and use of a business continuity plan based on sound principles, endorsed by senior management, and activated by trained staff will greatly reduce the likelihood and severity of impact of disasters and incidents.

One model is the plan developed by the Data Archive, and described in the DPC Case note on Business Continuity. Organisations may also wish to consider use of cloud services (see Cloud services) as part of their planning.

![]()

http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail?csnumber=50295

This standard provides general guidance for any organization to develop its own specific performance criteria for incident preparedness and operational continuity, and design an appropriate management system.

http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail?csnumber=54534

This standard specifies the requirements for establishing, implementing, maintaining and continually improving an information security management system. The requirements are generic and are intended to be applicable to all organizations.

![]()

http://dpworkshop.org/workshops/management-tools/disaster-preparedness

A Digital Preservation Management workshop webpage that links a set of 4 suggested documents (disaster plan policy, communications plan, training plan, roles and responsibilities). Cumulatively they provide comprehensive documentation and are updated to reflect current practice for disaster preparedness.

The National Archives provide two excel format self-assessment tools that link to its digital continuity guidance and framework of solutions and services.

The Self-assessment tool (0.4 Mb) divides the risk assessment into three sections: Understanding digital continuity and roles and responsibilities; Information requirements and technical dependencies, and Management

The Information asset risk assessment tool (0.26 Mb) helps you identify risks to the continuity of any specific digital information asset and identifies where continuity has already been lost. It makes recommendations on maintaining or restoring continuity to help you develop a digital continuity action plan.

This is an online toolkit for a digital repository audit. The toolkit guides users through the audit process, from defining the purpose and scope of the audit to identifying and addressing risks to the repository. DRAMBORA provides a list of over 80 examples of potential risks to digital repositories, framed in terms of possible consequences.

http://www.dlib.org/dlib/september12/vermaaten/09vermaaten.html

The SPOT (Simple Property-Oriented Threat) provides a simple model for risk assessment, focused on safeguarding against threats to six properties of digital objects fundamental to their preservation: availability, identity, persistence, renderability, understandability, and authenticity. The model discusses threats in terms of their potential impacts on these properties, providing several example outcomes for each. The article describing the model also included a useful comparison of other digital preservation threat models.

![]()

Includes a helpful risk assessment with many correlations to risk management strategies for Business Continuity Planning.

Assess and manage risks to digital continuity

The National Archives have built a self-assessment tool for the wider public sector that links to its digital continuity guidance and framework of solutions and services.

Assess risks to digital continuity factsheet

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/information-management/assess-dc-risks-factsheet.pdf

(2 pages)

Risk assessment handbook

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/information-management/Risk-Assessment-Handbook.pdf

(35 pages)

https://www.flickr.com/groups/2121762@N23/

This is a staging area for collecting visual examples of digital preservation challenges, failed renderings, encoding damage, corrupt data, and visual evidence documenting #FAILs of any stripe. You can contribute just an image, tell the story behind the image, or share the original file (or set of files), so that tool developers can learn from digital damage and test out their code with it.

![]()

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=25EhtuE3XkE

1 of 4 Business Continuity Management and the Digital Preservation of Processes webinars from the EU-funded Timbus project. This introduction is probably the most accessible for novices (released 2013. 13 mins).

![]()

The Data Archive is the UK national data centre for the Social Sciences funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). The Archive holds certification to ISO 27001, the international standard for information security, which requires information security continuity to be embedded in an organisation's business continuity management systems. The digital storage system at the Data Archive is based, for security purposes, on segregated and distributed storage and access. Business continuity at the Data Archive is based around the resilience provided by creating multiple copies of the data and specified recovery procedures, alongside pre-emptive failure prevention. Each file from any dataset has at minimum three copies. The Archive also creates a read only archival copy of each study and any update as it is made available on the system.

ISO, 2007. ISO/PAS 22399:2007. Societal security - Guideline for incident preparedness and operational continuity management. Available: http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail?csnumber=50295

The information provided in this section is intended solely as general guidance on the legal issues arising from various aspects of digital archiving and preservation and is not legal advice. It does not attempt to provide guidance on general legal issues which impact on the operations of libraries, archives and other repositories, as these are covered in a number of other reference works. It is written from a UK perspective and legislation in this area will vary from country to country. Although it principally covers UK and European legal issues, many of the topics will also apply in general terms to other jurisdictions.

An adviser–client relationship is not created by the information provided. If you need more details pertaining to your rights and obligations, or legal advice about what action to take, please contact a legal adviser or solicitor.

'those engaged in digital preservation must work within the law as it stands. This requires both a good general knowledge of what the law is, and a degree of pragmatism in its application to preservation work. Such knowledge enables the archivist to avoid the pitfalls of over-cautiousness and undue risk aversion, and to more accurately assess the risks and benefits of taking on the preservation of new iterations of digital work.' (Charlesworth, 2012, p.3)

Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) are a section of UK law that include patents, trademarks, copyright and associated rights - such as the moral rights of the author (see Stakeholders, contract and grant conditions) and performance rights. The preservation of digital materials often requires the use of on a range of strategies, and this creates IPR issues that are arguably more complex and significant for digital materials than for analogue media. If not addressed these can impede or even prevent preservation activities.

Among the range of IPRs, copyright has a specific importance when considering digital preservation actions. UK copyright law was developed with analogue material in mind. Traditional analogue materials are relatively stable, and well established legal and organisational frameworks for preservation are in place. The legal framework for undertaking preservation work on digital material is not as well developed and good preservation practices are not always recognised, or allowed for, by existing provisions in current legislation.

Copyright makes a distinction between ownership of the physical manifestation of a work, such as a book or work of art, and the separate right to reproduce it (the right to copy). Digital material by nature does not align to this distinction and can cause confusion when applied in the field. In the case of digital material, core repository practices such as providing access to users and routine preservation activities, often involve the deliberate or inadvertent creation of copies. Without appropriate rights clearance, licences or statutory exceptions these copies may constitute copyright infringements. Digital material therefore poses a different set of considerations for repositories holding this category of content. In addition, unlike physical material, digital material requires consideration of dependencies such as hardware and software which all have their own separate intellectual property considerations.

A second significant difference is the relatively short commercial and technological lifespan of digital material. The duration of IPR in digital materials extends beyond both commercial 'shelf life' and in almost every case the technology on which they depend. This forms a three-fold issue, in terms of procuring licenses to replicate content, licences for software to access content, and rights clearance of "abandoned" digital material, in addition to the added urgency of undertaking these actions.

Although the Copyrights, Design and Patent Act (1988) limits possible preservation actions for digital material, exceptions for archives, libraries and museums have been introduced to address the unique requirements for preserving it. From a preservation perspective the most important provision (Intellectual Property Office, 2014) is the right to produce any number of copies required for the purpose of preserving digital material. Another important exception is the dedicated terminal exception, which enables a digital copy (i.e. one of the copies created under the preservation exception), to be made available on a dedicated terminal accessible to walk in users. These provisions only extend to items held permanently in the collection. The exceptions enables those institutions covered by the exemptions to hold copies of material in various file formats and thereby adhere to what is considered good preservation practice while staying within the law. Note that the copyright exception provisions do not overrule the moral rights of the author which must still be considered when undertaking preservation work.

The exemption to copy for preservation does not however take into account the dependent nature of digital material, and third party software dependencies can still form a barrier to preservation actions. This is particularly an issue observed in preservation strategies which rely heavily on retaining the wider technical environment of the digital objects in question. For example, emulation as a preservation strategy requires use of original operating systems and software external to the repository's permanent collection (see Preservation action). It is important to consider the additional costs and time of maintaining relationships with third party rights holders that follow from dependencies not covered in the exceptions.

For institutions looking to publish digital surrogates of analogue material, the Orphan Works Licensing Scheme run by the UK's Intellectual Property Office, as well as the EU Orphan Works Exception are likely to impact digitisation work and planning. The Licensing Scheme allows for both commercial and (in the case of heritage institutions) non-commercial digitisation of any type of material in which it has not been possible to trace the rights holders of the material following a 'diligent search'. The licence is a pay scheme limited to a seven year period and for use exclusively in the UK. Repositories need to plan and budget for renewal of such licenses. The EU Orphan Works Exception, on the other hand, is restricted to text based and audio visual works only (and artistic works as long as they are embedded in the former), and museums, libraries, archives, educational establishments and public broadcasters. Here, the benefit is that the diligent searches are self certified and the preservation copy of the work, created under the preservation exception, can be placed on line for non commercial uses, for example, thus assisting greatly with digitisation activities.

Some of the additional complexity in copyright issues relates to the fact that digital materials are also easily copied and re-distributed. Rights holders are therefore particularly concerned with controlling access and potential infringements of copyright. Digital Rights Management technologies (DRM) developed to address these concerns and provide copyright measures, such as copy protection software for files and intentional physical errors to CD/DVDs, can inhibit or prevent actions needed for preservation. DRM technologies are also in themselves subject to obsolescence. These concerns over access and infringement need to be understood by organisations preserving digital materials when negotiating deposit agreements with rights holders, and addressed by both parties in negotiating rights and procedures for preservation. Having clear deposit procedures in place can mitigate future access issues (See Negotiating rights).

The legal status of web archives and processes of electronic legal deposit vary from country to country: some governments have passed legal deposit legislation but restrict access solely to library reading rooms. In others there is no legal deposit legislation and collections are either built solely on a selective and permissions basis or are held in 'dark archives' that are inaccessible to the public. In the UK, legal deposit libraries have the right to gather and provide access to copies of all websites published in the UK domain. However, access to the collection is restricted to library reading rooms (See Milligan, 2015). Parallel to this, Web Archives maintained by The National Archives (UK) operate with a smaller scope relating to government publications and clearer statutory powers derived from public records legislation (see Other statutory requirements).

The US-based Internet Archive, probably the largest and most used web archive, has no explicit legislative permission to harvest websites or to publish them. It operates on a 'silence is consent' approach, deleting from their collections any websites that an owner requests to be removed. In contrast, the Library of Congress operates on a permission basis meaning that they have to seek explicit approval from copyright holders before harvesting or publishing their content.

Other statutory requirements may also apply and influence preservation of digital resources.

The requirements of public records legislation and the related expectations of the Freedom of Information Act apply to government records including those in digital form. Statutory and regulatory retention periods apply to many digital records (e.g. for accounting and tax purposes). Although these are often of limited duration, it is notable that requirements for retention of digital records in some sectors (e.g. the pharmaceutical industry, social care and health records), are of increasingly long duration. In such cases long-term preservation strategies will apply as technological change will almost certainly affect access to such records.

Information may be subject to data protection laws and relevant privacy legislation protecting information held on individuals. In the UK, the Information Commissioner's Office oversees adherence to data protection and privacy issues.

Information can also be subject to confidentiality agreements. Privacy and confidentiality concerns may impact on how digital materials can be managed within the repository or by third parties, and made accessible for use. Data protection law also impacts on data movement outside of Europe - an important consideration for organisations investing in server space abroad.

EU rulings on an individual's right to have their personal information removed from Internet search engines in certain circumstances has a significant impact on the practices of organizations working with digital content sourced from the web (Koops, 2011). The obligation to avoid doing harm to individuals when saving their data over long periods of time is reflected in the principle of the right to be forgotten, through the implementation of Article 12 of Direction 95/46/EC in the case law of multiple European nations.

Some digital materials are the result of substantial financial investment by public funds (e.g. research councils) and/or publishers, and intellectual investment by individual scholars and authors. Each of these stakeholders may have an interest in preservation; the organisation preserving these will need to acquire permissions from them to safeguard and maximise the financial investment or the intellectual and cultural value of the work for future generations. Such interests could be manifested through contract, licence, and grant conditions or through statutory provision such as "moral rights" for the authors.

Holders of the material over many decades will almost certainly need to invest resources to generate revised documentation and metadata and generate new forms of the material if access is to be maintained. Additional IPR issues in this new investment need to be anticipated and future re-use of such materials considered. Where a depositor or licensor retains the right to withdraw materials from the archive and significant investment could be anticipated in these materials over time by the holding institution, withdrawal fees to compensate for any investment may be built into deposit agreements (See Negotiating rights).

As outlined in Legal issues, it is important that licensing issues, copyright and any other intellectual property rights in digital resources to be preserved, are clearly identified and access conditions agreed with the depositor and/or rights holders. If the legal ownership of these rights is unclear or excessively fragmented it may be impractical to preserve the materials and for users to access them. Rights management should therefore be addressed as part of collection development and accession procedures and be built in to institutional strategies for preservation. The degree of control or scope for negotiation that institutions will have over rights will vary but in most cases institutional strategies in this area will help guide operational procedures. It will also be a crucial component of any preservation metadata (see Metadata and documentation) and access arrangements (see Access).

As the volume of digital materials grows and the complexity of rights and number of rights holders in digital media continues to expand, ad hoc negotiation between preservation agencies and depositors and between rights holders themselves becomes more onerous and less efficient. This is particularly problematic for any UK organisations or activities not covered by the new copyright exceptions.

Development of model letters for staff clearing rights, model deposit agreements, and model licences and clauses covering preservation related activities helps to streamline and simplify such negotiations. Institutions should seek assistance from a legal advisor in drafting such models and providing guidance for staff on implementation or permissible variations in negotiations with rights holders.

A number of institutions have developed models which can be adopted or adapted for specific institutions and requirements. The procedures outlined below are a synthesis of current good practice.

The following provides a brief checklist and summary of legal issues which may need to be considered in relation to licences for preservation or deposit agreements for digital materials. Requirements will differ between institutions, sectors and countries and the list should be adapted to individual requirements. This list does not constitute legal advice and you must seek legal counsel for your specific circumstances.

IPR and digital preservation

A clause should be drafted to cover the following:

Access

Statutory and contractual issues

Investment by the preservation agency

UK legislation is regularly amended. To ensure that you are accessing the latest updates please refer directly to: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/

![]()

This guidance leaflet published by the Intellectual Property Office in 2014 sets out the exceptions applicable to libraries, archives and museums. It is relevant to anyone who works in or with libraries,

archives or museums in the UK, or copyright owners whose content is held by such institutions. In covers two significant changes in UK law which affect libraries, archives and museums. The first relates to making copies of works to preserve them for future generations. The second allows greater freedom to copy works for those carrying out non-commercial research and private study.

http://dx.doi.org/10.7207/twr12-02

This DPC technology watch report was published by Andrew Charlesworth in 2012. The document does not cover recent legislation (such as The Legal Deposit Libraries (Non-Print Works) Regulations 2013 and the 2014 Copyright Exceptions for Libraries, Archives and Museums), but is otherwise a relevant introductory work. The report is aimed primarily at depositors, archivists and researchers/re-users of digital works. Intellectual property law, represented principally by copyright and its related rights, has been by far the most dominant, and often intractable, legal influence on digital preservation. It is essential for those engaging in digital preservation to be able to identify and implement practical and pragmatic strategies for handling legal risks relating to intellectual property rights in the pursuit of preservation and access objectives. (54 pages).

These 2012 Proceedings include two papers on legal issues: Legal Alignment by Adrienne Muir, Dwayne Buttler, and Wilma Mossink (pgs 43-74); and Legal Deposit and Web Archiving by Adrienne Muir (pgs 75-88). The focus of the first paper is on the key issues of legal deposit, copyright exceptions for preservation and access, and multi-partner and cross-border working and rights management; the second paper discusses the challenges of adapting legal deposit a mechanism designed for print publishing to the digital environment. National approaches to key elements of legal deposit framework and the legal issues arising from non-statutory approaches to collecting digital publications for long-term preservation are identified.(342 pages).

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/CloudStorage-Guidance_March-2015.pdf

Table 3 provided in section 7 as an appendix to the TNA Cloud Storage Guidance published in 2015, lists legal points in greater detail for each of the three key categories:

http://www.create.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/CREATe-Working-Paper-No-3-v1-1.pdf

pages 6-18 of this 58 page 2013 paper by R. Deazley and V. Stobo, cover Copyright and the Archive sector within the UK.

This 2017 report by David Anderson of Brighton University and the E-ARK Project looks at legislation across Europe and its impact on Digital Preservation. The main part of this report covers the requirements of Directive 95/46/EC, which have been implemented by Member States in a variety of legislative instruments since the adoption of the Directive in 1995. These are set alongside the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) proposals currently under discussion between the Commission, the Council of Ministers and the European Parliament. As a final form of the text has not been agreed at the time of writing some of the conclusions reached in this report are necessarily tentative in nature.. (130 pages).

![]()

https://www.timbusproject.net/portal/domain-tools/334-lehalities-lifecycle-management-tool/

A tool developed by the TIMBUS project which looks at digital preservation of business processes. The areas covered are IPR, IT contracting, Data Protection and other statutory requirements.

![]()

http://livestream.com/unc-sils/iPres-Pamela-Samuelson/videos

Keynote presentation from iPRES 2015 by Pamela Samuelson, professor of Law and Information at the University of California, Berkeley. Samuelson has published extensively on IPR and Cyberlaw. In this presentation she considers the role of "fair use" in approaching the challenge that Copyright pose. Samuelson speaks from a US legal perspective but many considerations are also applicable in the UK context. (2015) 56 minutes

Charlesworth, A.J., 2012. Intellectual Property Rights for Digital Preservation, DPC Technology Watch Report 12-02. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.7207/twr12-02

Intellectual Property Office, 2014. Exceptions to Copyright: Libraries, Archives and Museums. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/375956/Libraries_Archives_and_Museums.pdf

Koops, B., 2011. Forgetting Footprints, Shunning Shadows. A Critical Analysis of the "Right To Be Forgotten" In Big Data Practice. SCRIPTed, 8:3, 229-256. Available:http://script-ed.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/koops.pdf

Milligan, I., 2015. Web Archive Legal Deposit: A Double-Edged Sword. Available: http://ianmilligan.ca/2015/07/14/web-archive-legal-deposit-a-double-edged-sword/

Organizations are increasingly interested in evaluating their digital preservation infrastructures against an assessment framework, and audit, certification, and self-assessment are hot topics in digital preservation. It is worth taking a moment to consider the difference between a self-assessment exercise and an audit.

Audit and certification is a formal process commonly carried out and delivered by external service providers. It is often a time consuming experience with exactingly high requirements that demonstrate to an external audience that a particular standard is being complied with.

Self-assessment is a precursor, or alternative, to a full audit and is typically delivered by staff inside of the organization, and the results are usually of highest value to the organization being assessed (rather than an external audience). Self-assessments can be useful in identifying practices which are underdeveloped and require improvement, particularly if an organization is interested in pursuing full audit and certification at a later date.

Many of the benefits can be summarised as ensuring that a repository can be trusted. The concept of a trusted or trustworthy digital repository is now broadly recognised in the digital preservation community. The following section summarises the work that has taken place over the past 10 - 15 years to get us to this point.

Audit and certification methods for digital preservation implementations have been in development for well over a decade with different organizations developing different methodologies in parallel. In Europe these are now coalescing under the European Framework for Audit and Certification of Digital Repositories.

The OAIS Reference Model (ISO, 2012a) (see Standards and best practice) influenced the development of the different methodologies, which began with the publication of Trusted digital repositories: Attributes and responsibilities (RLG/OCLC, 2002). This was refined as the draft publication An audit checklist for the certification of trusted digital repositories (RLG-NARA, 2005) before being finalised as TRAC (Trustworthy Repositories Audit & Certification: Criteria and Checklist) (CRL, 2007).